hat? You've never heard of

Tunnocks?’ Andy Partridge is simply flabbergasted. ‘Christ! It's

like not ever having heard of The Beatles.’ Shaken, he takes a

restorative cup of coffee. ‘They're biscuits,’ he explains,

recovering. ‘Caramel wafers with a red and gold striped pack. They're

made up north and they're heavenly. During recording we had at least

one a day apiece. Once you've tried them, you won't want to go elsewhere.

Believe me: after Tunnocks, all other biscuits turn into

Oasis. . .’

hat? You've never heard of

Tunnocks?’ Andy Partridge is simply flabbergasted. ‘Christ! It's

like not ever having heard of The Beatles.’ Shaken, he takes a

restorative cup of coffee. ‘They're biscuits,’ he explains,

recovering. ‘Caramel wafers with a red and gold striped pack. They're

made up north and they're heavenly. During recording we had at least

one a day apiece. Once you've tried them, you won't want to go elsewhere.

Believe me: after Tunnocks, all other biscuits turn into

Oasis. . .’

Welcome to XTC's world headquarters - which isn't on the camera-clicking

tourist charabanc route, but certainly should be

(‘. . . and on the left, ladies and gentlemen, the shed

affair by the side of the fine Victorian-era villa hides the trembling heart of

true English pop music. Now, if you direct your gaze over to your right,

you'll see an actual English sheep. . .’). XTC central, you

see, is actually bassist Colin Moulding's garage - a modestly-sized outbuilding

nestling close by his house in the hollow of a misty green Wiltshire hill.

Luckily, instead of the bags of manure and past-it gardening implements

you'd have found here last year, it now contains plenty of fresh wood

panelling, nice orange-painted walls and a compact array of modern beat-group

recording hardware. It's all delightfully civilised: an eccentric, brilliant

‘We make very light music. It doesn't take itself too

seriously. We're not like Radiohead. We're a little more breezy about the

whole business’ Colin Moulding

duo welcoming the attentions of the gentlemen of the press. Moulding, a

picture of casual elegance and friendly reticence, offers chicken sandwiches.

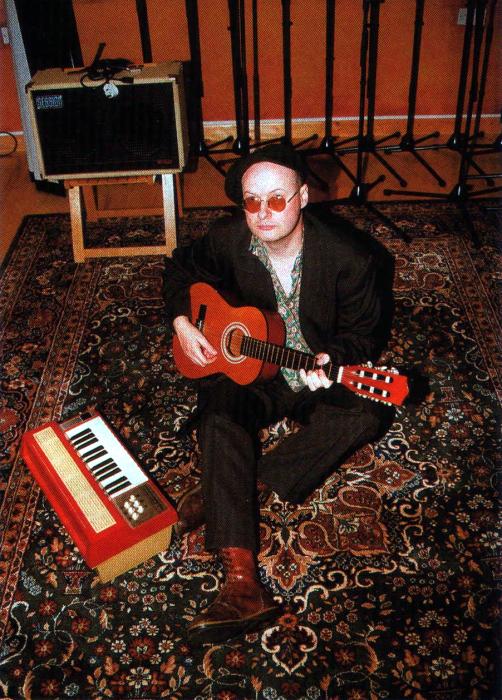

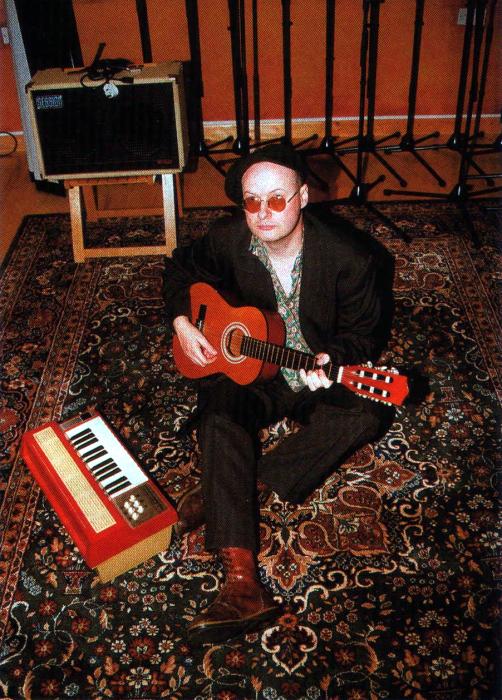

The more extrovert Andy Partridge, floppy velvet cap cheerfully askew, strums a

£20 classical guitar and free-associates like a bastard.

For legions of XTC fans the world over, this is hallowed ground. This -

thrills! - is where the pair crafted the bulk of Wasp Star (Apple Venus

Volume 2), a delectable array of songs laid down with a simplicity, verve

and renewed dedication to the joyous tones of the electric guitar that will

remind XTC fans of their most-dusted LPs: Black Sea, Big Express,

Skylarking, Apples And Lemons [sic]. It's pop music that's

heartfelt, beautifully crafted and stunningly arranged. It's also pop music

borne out of a period of considerable strife.

In 1993, worn to the point of exhaustion battling one of the most notorious

and unrecoupable record contracts of the last 30 years, XTC went on strike. No

records, no anything: just silence. After two unproductive years, Virgin

finally agreed to let the trio go. The band signed to small labels Cooking

Vinyl in the UK and TVT in the States and set about making sense of a

considerable backlog of songs.

The next bit is complicated. First, the plan was for a double album. With

cash from Japanese label Pony Canyon the band hired favourite producer and

orchestra expert Haydn Bendall, blew two months getting nowhere at

Squeezeperson Chris Difford's studio, then moved to Chipping Norton - the

famous Manor of Richard Branson and Tubular Bells fame (some material

from this period would eventually end up on both albums). Then the money ran

out. More dosh arrived via the TVT deal, but then Bendall was forced away to

fulfil other commitments. XTC were stuck with one quarter of a double album,

and the pennies were trickling away.

famous Manor of Richard Branson and Tubular Bells fame (some material

from this period would eventually end up on both albums). Then the money ran

out. More dosh arrived via the TVT deal, but then Bendall was forced away to

fulfil other commitments. XTC were stuck with one quarter of a double album,

and the pennies were trickling away.

It was Colin Moulding who had the brainwave. Turfing some junk out of his

front room, the band draped cables across the hallway and installed a desk,

some mics and a little amplifier; Nick Davies, the man who'd mixed 1992's

Nonsuch, assumed the producers' creased forehead; and XTC did the rest

of the album, now trimmed to a single volume, right there, Hollywood-style,

save for one hectic day herding an orchestra into Abbey Road.

As it turned out, Apple Venus (Vol 1) was a chamber-pop triumph:

delicate, sumptuous, an astonishing record. But there had been casualties -

and the most serious was the loss of long-serving guitarist Dave Gregory.

Frustrated at his increasingly keyboard-playing role, stressed concerning the

band's new orchestral direction, Gregory fell out heavily with the hugely

talented but famously difficult Andy Partridge, departed to continue his

successful session career and hasn't spoken to XTC's lead songwriter since.

The obvious irony is that had Dave Gregory managed to stick it, the long

awaited second half of the original double LP, Wasp Star (Apple Venus Vol

2) - rockier, stripped down, crammed with guitars - would have been right

up his street. This album was assembled not in Moulding's parlour but in the

all-new garden studio. And, just as you would be, Partridge and Moulding are

rather proud.

‘We could have done this ages ago, but we always had people like

Virgin going “don't blow it on your own studio! We've heard too many

horror stories about that,”’ mourns Partridge. ‘But it

actually saves us about a thousand pounds a day. The whole cost was

£30,000, say £40,000 with

‘Bands are gangs with guitars instead of knives. You're going

out to drink the world dry, shag all the girls and deafen their dads. Then you

grow up a bit and go, hang on. . .’ Andy Partridge

equipment, and that's just one month's studio time in Chipping Norton - or half

a month in Abbey Road. But we're very conscious of not sitting around drinking

tea all day long instead of recording just 'cos we've got out own studio - and

we didn't have Nick booked forever. So we worked from 10.30 to 6 or 7 at

night. Gentlemen's hours.’

But isn't it remarkable that the room sounds so good, seeing that rather

than acoustic loveliness the space was, strictly speaking, designed for two

Ford Escorts?

‘Escorts?’ complains Moulding, miffed. ‘Volvos,

please.’

‘I think Escorts is much more like it,’ cackles Partridge

unkindly. ‘But, yes, we've been jammy. The wooden floor is much less

pingy than a concrete one would be - it's fabulous for acoustic guitar and the

drums are the best we've had on a record. Mind, some of that is down to the

Radar hard disk recorder, which is lovely - it sounds like a tape machine,

quite warm and not at all fizzy or harsh. Plus you can move everything around,

and it's the first time we've had that.’

|

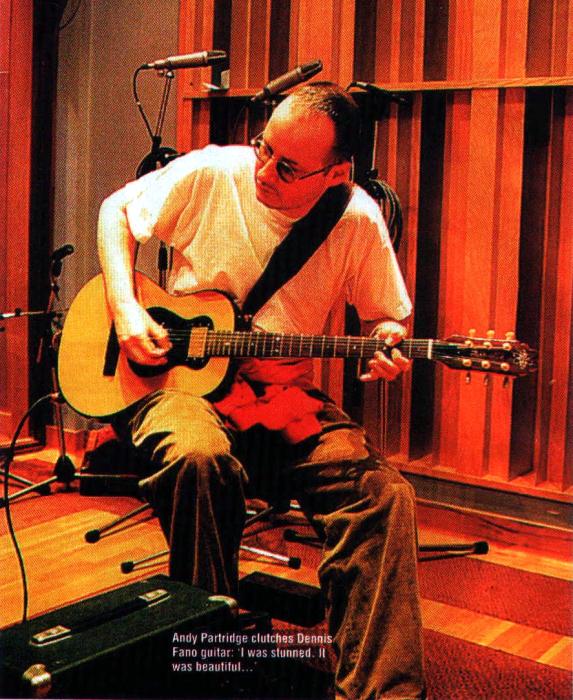

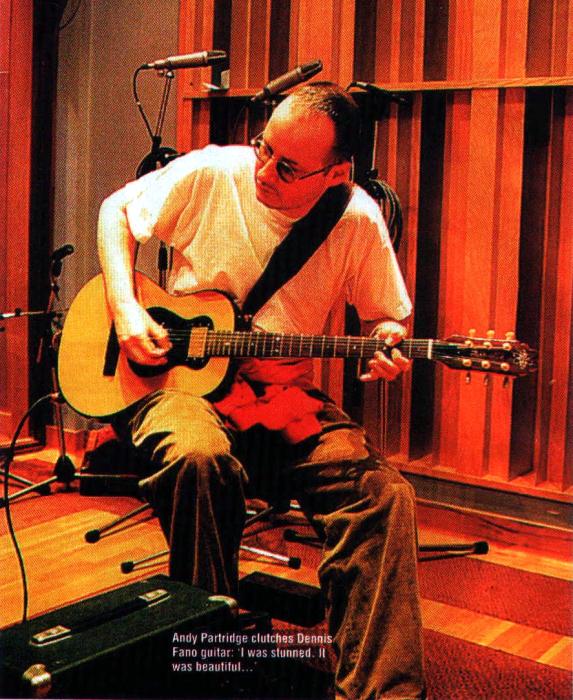

| Photo: Meridith

Fano |

Andy Partridge

clutches Dennis Fano guitar:

‘I was stunned. It was

beautiful. . .’ |

|

Fingers Working Overtime:

THE XTC GUITARFILE |

|

With the departure of Dave Gregory XTC have lost a

considerable arsenal of vintage sounds, including Andy Partridge's favourite

amp, a Fender Super Reverb. But they get by - and a mad XTC fan and

guitar-builder in New York has helped them out in the best way

possible. . .

Partridge still owns and plays his venerable '75 Ibanez Artist (the

newly-released song My Brown Guitar is not, sadly, a tribute to this

long-suffering instrument but a paean to the Partridge todger). His main

acoustic is an early '70s Martin D-35, his only bass a Kay-badged Woolworth's

model (‘it's plywood . . . sounds like a tuba’).

Strangely, his most-played guitar of recent years is a cheap 3/4 sized

Romanian classical belonging to his daughter Holly, a guitar which led directly

to his latest acquisition - see the picture above.

‘A musician friend, David Yazbeck [sic], was visiting Matt

Umanov's guitar shop in Manhattan and noticed one of the guitar repairers there

had an XTC tattoo,’ explains Partridge. ‘David mentioned he knew

us, and the guy fell on the floor saying he'd always wanted to make a guitar

for us. So I got a phone call from this chap, whose name turned out to be

Dennis Fano, and he offered to make me a guitar, and I tentatively said,

“Well. . . um. . . okay, then,” and when he

asked what kind of guitar I wanted I ended up talking about this cheap

classical that I'd been playing.

‘To be honest, I wasn't expecting much of it - you know, maybe a cigar

box with some rubber bands on it - but it turns out that Dennis is a fantastic

guitar builder. This incredible electric guitar arrived with the same body

proportions as the classical and all the controls on little wheels around the

edge to keep the looks clean. I was stunned. It was just beautiful. He's

making me another one, too, although I tried to refuse - they're worth a grand

and a half, easily - and this one'll be based on his standard model, the

Satellite, in glorious Las Vegas-style white, which is the colour guitar I've

always wanted.’

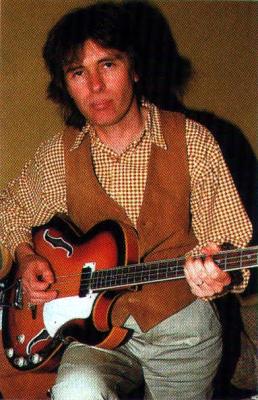

‘Dennis made me a bass, too,’ chips in Moulding. ‘I

haven't quite got used to it yet, but it's beautiful and it's on some of the

new album. It's based roughly around my favourite bass of the moment, a 1969

semi-acoustic Vox Apollo which was a present from T-Bone Burnett. It was named

Apollo for the moon landings, I believe, and it's especially nice between the

5th fret and the octave. I'm very enamoured of it. . . it has a

lovely roundness and richness. I also used the old Epiphone Newport - it's got

a damper at the bridge that makes it sound like an old upright bass. That's

the one I used on The Man Who Murdered Love and We're All

Light.’

Moulding's amplifier is a 100W Gallien Krueger combo which Partridge has

dubbed the ‘GK Chesterton’ (‘It looks like a chest and it

says “GK” on the front,’ he explains, plausibly), while the

Moulding demos are pieced together with a Squier Tele and a Takamine

electro-acoustic.

Our thanks to Dennis Fano. Check out www.fanoguitars.com

|

|

Wasp Star find Andy Partridge holding his end up as one of this

country's most original and underrated guitarists, by turns unnervingly precise

and wildly off-the-wall, from strutty, staccato knee-level rock riffs to

fuzzed-out hooks and chiming arpeggios, chunky rhythm parts and compelling

solos (the one on Church Of Women sounds like Larry Carlton's mad

axe-wielding cousin). It's also crammed with a brilliant array of distortion

sounds. The key? A wee device you can buy yourself for a few hundred quid:

the Line 6 Pod. Partridge can't splutter highly enough about the little red

kidney-shaped sound-tweaker.

‘Everything on the album went through the Pod,’ he

explains. ‘I'm not joking. Vocals, bass, drums, keyboards, percussion.

Distortion is the absolute key to making great records. Listen to your fave

Tamla records: fuzzy drums, distorted vocals, fuzzy bass, and the whole thing's

fuzzed up and compressed to buggery on top of that. Back in the days when

everyone went through amps in the studio it happened naturally. Now

everything's DI'd and super-clean and people wonder why things don't have any

life to them.

‘Discovering the Pod solved my amp dilemma. Before I used to borrow

Dave's Fender amp and use my Ibanez Artist and a Korg compressor and that sort

of screaming result was basically my guitar sound. Now we've got all these

subtleties of distortion, and it's really potent.

‘The other key sound on this album was the way we recorded a lot of

electric guitars: we positioned a microphone about an inch from the body to

pick up all those super-clean acoustic highs that you'll never get through a

pickup, and mixed that with the regular electric sound which was usually the

Pod on some really distorted setting.’

‘It's like a Kinks guitars sound,’ ventures Moulding, ‘not

electric, not acoustic, more steel-electric or fuzzed-out-acoustic. It's on

In Another Life, We're All Light, Boarded Up, The Man Who Murdered Love.

It's the real backbone sound. If you can find that backbone, you've got a

song.’

‘The whole thing about Volume 2 is that it's working with a

more selective palette than Volume 1,’ points out Partridge.

‘The first was wide-screen, in full colour, acoustic and orchestral: this

one was intended to be more a play made for television in black and

white.’

So are Messers Partridge and Moulding fully prepared for the all-engulfing

wave of love that will surely follow this masterfully televisual musical

release?

‘Engulfing love?’ hoots Partridge. ‘The only engulfing

love we get is Japanese or American! We can't get arrested over here. We're

only big amongst people who get their records for free.’

‘Journalists do like us, it's true,’ considers Moulding,

‘but I think they've logged on to cool bands like Blur saying they've

been influenced by us and praising us to the skies. They've never been sure as

to whether they really like us or not. Ours has always been the three

and a half-star review. With a sarcastic line to balance it out.’

Is XTC's old ‘too clever’ tag the underlying problem?

‘That “clever” thing has dogged us from the very beginning

and it's rubbish,’ opines Partridge firmly. ‘We're council-house

chaps. We left school with no pieces of paper whatsoever. Our intelligence is

something we've garnered over the years and we won't play dumb, not for anyone.

We just do the best we can. That's our ethic.’

‘I think perhaps some people don't really know how to take bands that

have a lightness of touch about them,’ offers Moulding. ‘We make

very light music. It doesn't take itself too seriously. We're not like

Radiohead or other bands that critics love so much because they're so into

their “art”. We're a little more breezy about the whole

business.’

‘This thing about fake seriousness really bugs me,’ agrees

Partridge. ‘Lots of bands at the moment only dabble in goatee-bearded

“serious” music 'cos they imagine people will take it as art. What

they're doing is denying the thousand other thoughts they have every day, like

“Aren't those tits fabulous?” or “I wonder where I can get my

shoes mended?”

‘I do understand it, because when I was 18 years old I was just the

same. Nobody took me seriously, so I washed myself in serious books, serious

records: that was my camouflage. But what I really liked were fun things like

comics and stupidness. You're less honest with yourself when you're younger,

because you don't know yourself. But people that make a career out of being

less honest than they could be - aargh!

|

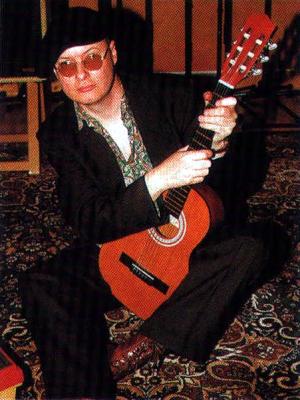

Moulding's Wasp

Star basses: Dennis Fano custom, Epiphone Newport with cool plonky

string damper, and super-hip '69 Vox Apollo, a prezzie from T-Bone

Burnett |

‘I'm not asking for total honesty,’ he continues, warming to his

theme, ‘because human beings can't be completely honest - if we were,

civilisation would break down. Instead of saying “Good morning!”

we'd all be swearing and telling each other where to get off. We've basically

all agreed to lie to each other. . . it makes day-to-day living

rather easier. But what I want artistically from someone is contact with that

person's soul, a real musical honesty. XTC have always tried to be honest,

even when people thought we were just smartass annoying little

artpunks.’

And Wasp Star is, indeed, honest - sometimes brutally so.

Partridge's Wounded Horse (on the subject of unfaithfulness) will make

you suck your teeth; Playground (‘marked by the masters and

bruised by the bullies’) comes arrow-straight from childhood. Balancing

these are Moulding's own sturdy contributions. Boarded Up mourns the

demolition of most that made Swindon life bearable, while the married-life love

song In Another Life (‘I'll take your mood swings if you'll take

my hobbies’) darn near steals the whole show.

‘I always think that writing from the personal angle makes most

sense,’ Moulding points out. ‘It's the small things that matter.

You may want to write about the world and war and all that, but does it really

make contact with people? I don't think it does.’

‘You do get more into writing from personal experience - more up

yourself, if you like,’ adds Partridge. ‘That side gets more

important and you get more selfish, more particular about what you want and how

you're digging this stuff out of yourself. I was pushed around at school,

hence Playground, and now I advise my own son to smack any bullies right

in the teeth as fast and hard as he can - which is the exact opposite of what

my parents told me. Stupidly Happy is about a feeling that everyone

knows, that initial idiot trance state of falling in love. There's nothing on

the album that hasn't been gone through. Funnily enough, I used to write about

what I thought would happen - and now it's more things I've done.’

If there's one bone that XTC lovers refuse to surrender, it's the subject of

whether their beloved combo will ever play live again. The occasional promo

jaunt and radio appearance aside, the band haven't trod the boards since 1982,

the year when Partridge's aversion to stage appearances reached breaking point.

XTC have flourished for 18 years as an in-studio outfit and spent only five

years actually gigging, so it's a question the duo find somewhat

perplexing.

‘I met a German guy last week who was on about it,’ recounts

Partridge. ‘I said, why do you want to see us live, then? And he said

(very decent German accent) “Well, I and my friends will get very

drunk and you are playing the soundtrack to this!” And I thought, hang

on, we don't want to be the soundtrack to your piss-up! It's not of interest,

to be honest!’

|

| ‘We're council-house chaps. Our intelligence

is something we've garnered over the years and we won't play dumb, not

for anyone’ Andy Partridge |

‘Even after all these years, my mum still thinks we go on tour,’

recounts Moulding wryly. ‘I say, I'm off to America, mum. “Oh,

are you? Off on tour?” No, mum, we don't actually do that these

days. . .’

‘At that age, they think if you haven't got any bookings over

Christmas, you've fucked it,’ cackles Partridge. ‘My dad still

says “You got any shows over the New Year? No? You want to get hold of

the MU man, he'll fix you up. . . you'll get cash in hand,

sandwiches. . .” If you ain't got bookings, you've had it.

Haha! But the thing is, gigs are all good fun when you're young. Bands are

like gangs. You've got guitars instead of knives and you're going to go round

the world and drink it dry and shag the girls and deafen their dads. Then you

grow up a bit and go, hang on. . . I don't want to be in a gang

anymore.’

‘Instead, we became fascinated by records and finding out all the

secrets of how that magic gets into your ears,’ explains Moulding.

‘When I heard Strawberry Fields as a kid I could not work out

how they got those sounds,’ agrees Partridge. ‘Now I know it was a

Mellotron on the flute setting, backwards cymbals, sped-up brass, cellos, all

that. As a kid I went, how can those noises exist? I love it!

‘But it's like an apprenticeship, making records. If you're going to

do it, you need a long time to find out how to do it. It's an alchemy, this

business. It's not real, just like making a film is not real. There are

people who still imagine that a group of actors play a scene, then they switch

the cameras off and go and do the next scene. That's not how it happens. You

make films by gluing bits together that are just right. They have to support

the other pieces, they have to lead you forwards, the scenes have to be

correctly lit. Records are the same - I'm sure some folk think you go into a

studio with a three-pin plug dangling from your guitar, plug it into the wall

and out comes our record. . .’

‘People think the process is fake, and in a way it is,’ points

out Moulding, ‘but what you're trying to do it make someone feel

something. You're creating something that'll touch that tender spot. And

that's very real.’

How true. And how good to find the entirely unique XTC in a better position

than at any other time in their 25 year history: wondrous hard disk recorder

bought and paid for, bonkers and thus entirely suitable new guitars in hand,

personnel trimmed but stabilised, songwriting ready to flourish again (Andy

Partridge is threatening ‘something really crass. . . I still

fancy doing an even more simplistic bubblegum thing. Or maybe some ambient

operatic psychobilly’). Watch that garden shed.

Rick Batey