GUITAR PLAYER June 1992

Andy Partridge blows his nose and apologizes — “I've

got an atrocious cold. I feel like a 20-watt bulb, rather than my usual

halogen lamp.” In his charming Swindon accent, he speaks with the same

mixture of honesty, wit, and cynicism that has marked 15 years of guitar

playing and songwriting with the critically acclaimed, fanatically revered, and

criminally undersold British pop trio XTC. ![]() Partridge's sniffles are hardly

likely to slow down his ebullient personality; some might even say he's always

complaining about something, and this is what gives him his edge. When XTC

released its debut White Music in 1977, it was up-your-nose new wave at

its best: quirky, jerky, sometimes obnoxious, and rhythmically defiant,

suturing mulched Ska beats onto barking seal vocals and jagged, bravely angular

guitar jabs. But some bubbling interior forces were at work inside Partridge,

both musically and personally. by james

rotondi

Partridge's sniffles are hardly

likely to slow down his ebullient personality; some might even say he's always

complaining about something, and this is what gives him his edge. When XTC

released its debut White Music in 1977, it was up-your-nose new wave at

its best: quirky, jerky, sometimes obnoxious, and rhythmically defiant,

suturing mulched Ska beats onto barking seal vocals and jagged, bravely angular

guitar jabs. But some bubbling interior forces were at work inside Partridge,

both musically and personally. by james

rotondi

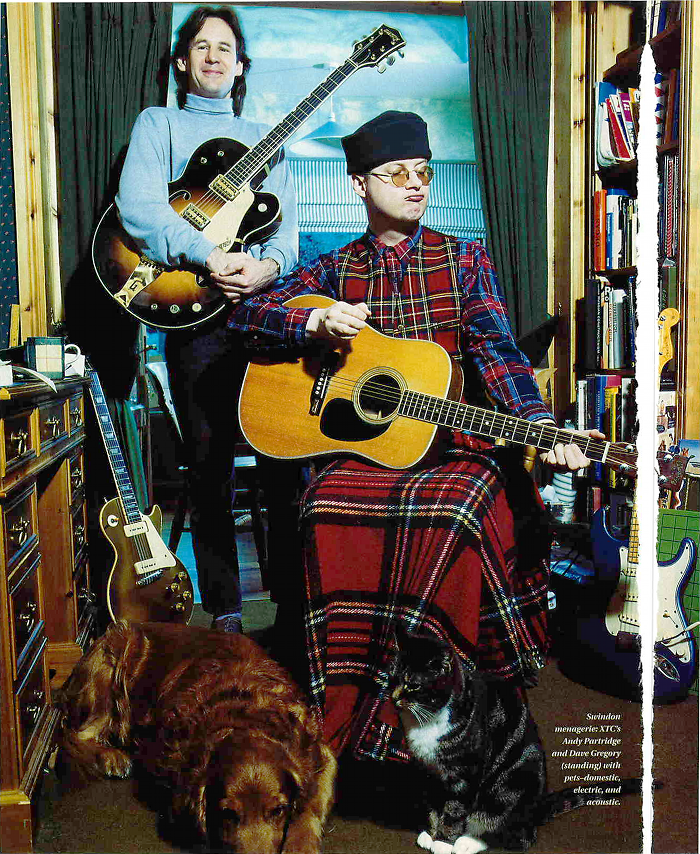

Swindon menagerie: XTC's Andy Partridge and Dave Gregory (standing) with pets: domestic, electric, and acoustic.

photography by paul rider

1979's Drums And Wires saw the inclusion of new guitarist and keyboardist Dave Gregory, an increased tendency towards the melodic pop staples that satiated Partridge as an adolescent Beatles fan, and a nagging distaste for the stresses of live performance. The record produced bassist Colin Moulding's hit “Making Plans For Nigel,” and turned up the heat on a gestating public demand. Black Sea continued the progression, providing instant melodies like “Majors And Generals” [sic] and clean, pretzel-knotted guitar figures that chomped at the bit of tight, exacting rhythms.

Then, following what many consider their watershed LP, 1982s English Settlement (which yielded the Top 10 hit “Senses Working Overtime”), XTC as a live band suddenly screeched to an agonizing halt: Andy Partridge was mentally and emotionally exhausted, a condition the band would later describe as “something of a breakdown.”

“People come from all around the world and stand there outside my house, which really gives me the willies,” Partridge recounts good-naturedly. “But I'm very tender with them. I can see they're probably sweating profusely, shaking, and about to have some sort of brain hemorrhage any second now.”

“I just don't like the ‘Hey, look at me, I'm fantastic!’ show-biz thing”, Partridge says now of his ongoing refusal to gig. “I have terrible stage fright, I hate touring, and I consider myself a songwriter, not a sweaty, ass-wiggling gorilla up there in the spotlight.” Though it lost them drummer Terry Chambers, XTC's ban on concerts has graced them with two mixed blessings that the Beatles received when they swore off public appearances: an increased ability to dedicate creative energy to the studio, resulting in masterpieces like The Big Express, Mummer, and the Todd Rundgren-produced Skylarking and an intensified cult following willing to literally go great lengths to commune with their demigods.

Andy Partridge's approach to gear is as irreverent as his philosophy: “Most of my guitars have been phenomenally crap, like a Futurama guitar I had painted leopard skin. I had a Singapore guitar called a Sway Lee Goldentone — one of those really badly made guitars that as you go down the fretboard towards the nut end it gets wider! I had a homemade Flying V that was four times too thick. It was like a couple of railway slivers joined at the hip. I did White Music and Go 2 with a 1975 Ibanez Artist. I've recently brought it back from the dead, and I played it mostly on Nonsuch — plus my usual Squier Telecaster, my main guitar since 1983.”

Andy's amp is a Session 70 (“the cheapest thing in the shop”), although in the studio he covets Dave's 40-watt 1963 Fender Super Reverb. “I'm pretty much compression crazy,” he admits, “putting the compression before the amp. You can crank it up and get a smoother shape. On this record, I recorded a lot of echoes as part of the rhythm. There's some E-bow on ‘The Ugly Underneath’ — that high, spooky, dissonant orchestral stuff. My acoustic is a Martin D-35. I don't really have a head for gear. I mean, I've written albums on 5-string guitars because I was too lazy to put another string on! Dave is the real equipment guy. You and him can talk dirty about guitars.”

Dave Gregory's large collection boasts some vintage cream puffs: “The guitars of the '50s and early '60s were some of the best-looking things I've ever seen”, he enthuses. “My first Gibson was a cherry-red '64 SG Standard with a Maestro tailpiece. I've also got a Les Paul Junior from 1965, with a single P-90 pickup. But if I want a P-90 sound, I use my '53 gold-top Les Paul. If I need a big, warm, fat rock and roll sound, that's the guitar I go for.

“I've got two Rickenbacker 12-strings: an old 330 from 1964, which was one of the first in this country after A Hard Day's Night launched them, and a black 360 12-string I bought to record English Settlement.”

For Nonsuch, Gregory played his trusty old gold-top as well as a '63 Epiphone Coronet Dwight, a '65, a '65 Fender Jaguar, a Vox Phantom and, on “The Ballad Of Peter Pumpkinhead”, a Gretsch Country Gentleman. On the “That Wave” solo, he played a Stratocaster through a Roland JC-120 amp in admiration of Adrian Belew's tone on King Crimson's Beat.

Like Andy, Dave's a big fan of the Boss CE-2 compressor pedal, and he recently invested in Korg A2 effects processor. He uses Ernie Ball strings with unusual gauges: .011, .013, .016, .026, .038, .050. “I like heavy bottom strings,” laughs the genial Englishman. “That's root of your chords, man. They've got to be down there.”

Coming three years on the heels of Oranges And Lemons, XTC's new double LP Nonsuch features 17 enigmatic and catchy tracks fleshed out with the help of Fairport Convention drummer Dave Mattacks. The album gives long-waiting fans plenty to chew on, and provides fanatics more to feed the fire of their zealousness. Despite the godly treatment, Andy insists that XTC's lifestyles are of the backyard garden variety: “We're really so horribly normal, just kings of the mundane. They should see me sitting up in bed farting, with a six-pack. They'd realize how un-‘star’-ish it all is.”

Andy Partridge: An Audience with the Mayor of Simpleton

Along with your great pop sensibility, you sound like you have a background in jazz.

I have a very split background. One half of me wanted to be in the Monkees, and use the guitar as a fishing rod to get girls out of the water, go back to the group house where we all lived together, wear the group uniform, have the group haircut. I used to do everything I could — and I was pretty passable — to look like Peter Tork. I had the haircut, and from my mother's mail-order catalog, I got a shirt with a double-breasted panel and the hipsters with the big, wide plastic belt. I was living the image in 1967 and 1968.

Not long after, I struck up a friendship with a rather bohemian character known enigmatically as Spud Taylor. He used to get a lot of very bizarre import things: jazz on the avant-garde side, stuff coming over from New York. So I would get exposed to a lot of out-there stuff. Sun Ra was quite shocking. I heard Captain Beefheart And His Magic Band's Trout Mask Replica for the first time. These were albums that stuck with me forever and ever — Sonny Rollins' East Broadway Run Down, Tony Williams Lifetime's Emergency with John McLaughlin, Larry Young, and Tony Williams.

It split me pretty badly because I was trying to learn from the pop technicians, the Jimi Hendrixes, the Jimmy Pages, the Rory Gallaghers, mixed in suddenly with this enormous dollop of melodic jazz scribbling, and I was trying to fashion songs out of it that wouldn't go amiss in the Monkees. XTC came out of that eventually.

You had a very rhythmic style in the early days, very influenced by Ska and New York new wave.

It came from wanting the guitar to be a rhythm instrument. I didn't want to play the same backbeat as the snare drum, so I found the holes between it so you could hear what I was playing. And it made a funk. I still look for the holes to make the funk. My first thought was, “How do me and the drums marry?”

The guitars are scaled back on Nonsuch; the parts are more essential.

I'm getting more into accompaniment and song construction. Melody has become more important to me. I used to think in much more rhythmic terms. At one point, I wanted to be a Charlie Parker of the 6-string. “Don't tie me down with those rotten song restrictions!” But as time's gone on, I find I get immense joy from basic building-block song constructions — a big slab of blue there, piece of yellow there.

I still enjoy scribbling with the guitar, but in the wide world of song building, it's much better for me to think in bigger, easier chunks. Not that bigger chunks means “lazy.” I'm actually getting much better at putting chords together, putting up a great set of bars for the voice to climb onto. You have an idea of where you want to climb, and you have to put these well-bolted, confident monkey bars under it or else the climber is going to stumble.

You do have a great knack for irreverent playing.

Well, if you want to poke your tongue out you should poke it out. I don't like to be trapped in key. Keys are boxes. They're okay, you can use them, but it's also fun to jump out occasionally. I love chords that have triangular, star-shaped points to them. I'm not keen on the round ones that just slip down, porridge-like. I like chords with a bit of dissonance and pungency — they're not afraid to kick their legs out and show you they're alive. I like to find ways of stumbling upon chords of this nature or bizarre ways of arriving at really safe chords; unusual tunings can do this for you.

What guitar roles do you and Dave take?

Colin Moulding and I write songs and blunder about bravely, but Dave is the musician/arranger/guitar man. I'm slashier and more irregular. My playing goes through the rhythm and meanders — blunders — through the key. He's smoother and more rhythmic, and he always seems to know where he's going. At one time it was purely workhorse stuff. If I was singing a song, I would play the simpler thing. But it's not portioned to “I'm guitar A, he's guitar B. Throw the switch!” People think that when you play, you're listening. But it's not always true — you're playing, you're feeling, becoming part of the instrument — you're not necessarily listening.

That's the ideal, though, isn't it?

Yes, but it's tricky to criticize and perform. You can't wear the two hats simultaneously. To perform you have to shut off the critical muscle. If you don't, your performances will come out dull and uninspired, and there'll be no wonderful accidents that might lead you up another alley. I suppose it's invention, really; invention being mistake.

So does the band still rehearse as a group?

Absolutely. There's nothing worse than being in the studio and not knowing what you're doing. It's like wandering into a lavatory and saying, “Now what did I come in here to do? I'll get it in a minute if I just hang around this toilet bowl. Something's bound to come to mind.” We go in the studio with our purposeful heads on pretty firmly.

What gives birth to your songs? A riff or a chord?

Riffs are usually found to fit into a song at some point. Songs grow from a chord you hit and think, “Hell, that chord sounds just like a . . . wet afternoon — that's such a rainy chord.” And then your brain starts spewing out rainy afternoon stuff and you start looking for chords that illustrate the words that have just fallen out. Raindrops! Whoah, rain! Aaaaah! Then it all comes out. It's like vomiting. Once you know it's on its way, there's nothing you can do to stop it.

Some of your songs reveal that you have a certain . . . uh, wounded instinct.

What do you mean? [Bursts into laughter.]

In 1984, XTC indulged in two weeks of unabashed fantasy realization. Dubbing themselves The Dukes Of Stratosphear, they knitted a sonic quilt of psychedelic threads called 25 O'Clock, weaving every '60s acid-pop group they'd loved as kids into a brilliantly exciting tribute/satire.

“There's Syd Barrett's Pink Floyd, the Yardbirds, plenty of psychedelic Beatles, the Byrds, the Hollies — the criteria was to use older guitars, older amps, and older techniques,” recalls Partridge of the John Leckie-produced EP. “We used the old thought as well. Everything was first take, which adds to that off-the-cuff feel a lot of those old records had.

“The Dukes was a band we wanted to be in as kids — literally. It was like, “Wow, when I leave school and get a guitar and amplifier, that's what I'm going to do!’ you don't consider getting older, situations changing, tastes changing. And then you didn't get to be in The Dukes of Stratosphear. We thought we'd correct that.”

After the EP's surprise success, XTC was beseeched to do more: “It was such intense fun doing 25 O'Clock, and so many people said, ‘Ask the Dukes to do more’,” laughs Andy. “Like they lived in our wardrobe or something!” Psonic Psunspot became the first Dukes Of Stratosphear LP, and it is now joined by 25 O'Clock on the very un-'60s CD format as Chips From The Chocolate Fireball on Geffen.

Partridge insists that the Dukes have fuzzed out to that great crash pad in the sky: “They died in a bizarre cooking accident. We whisked them to death.”

Well, even on the newest record, you call yourself the “spokesman of the disappointed” and you claim to “resign as clown.”

You're right. I must have been stomped on a lot by females earlier on. I'm still getting stomped on. I idolize women. Maybe that's why they stomp on me. I seem to continuously put myself down as some kind of doormat for them. I'm stunned. I'm speechless. I must have a wounded psychology.

I didn't mean to pry.

No, doctor, it looks like you've hit the nail right on the head there. [Laughs.] You've hit the phobia right on the Napoleon!

Who is the song “The Ballad Of Peter Pumpkinhead” about?

People can put to it who they want, but it's really about a pumpkin. I carved a lantern for my kids on Halloween. When Halloween was over, I didn't have the nerve to throw it in the bin so I took it in the backyard and stuck it onto a fence post. The weeks went by and it rotted, and every day I'd walk past it to go down to the shed at the bottom of the garden where I compose, and I started feeling sorry for this pumpkin. I thought, “I'm going to make him the hero of this song.” He only had a very brief life. He went a gray-green fluffy fur color and collapsed in on himself. A bit like me, really.

Does the song also come out of a feeling for what happens to people who fight for truth?

People who fight for truth never win because nobody wants to know the truth. It's too powerful. We can't know the truth, so we make up everything else instead. We live out all these various lies through everything, whether it be religion or politics. And too many people get “belief” mixed up with “truth.” It's a protection device. It's also to look for a reason for being here in the first place — which I don't think there is. Mankind thinks it's been put here for some reason. My own untruth/truth, my own belief, is that we have no purpose, that there's no reason why we are this shape. It's man's arrogance that has invented God and the Devil that looks like him.

I think we should have some basic human rules. One of them is don't hurt other people, because they're only having their one chance like you. So have fun and give other people fun along the way. But all this “God” and “our special purpose” — come on. Wake up.

Dave Gregory: The Quiet Craftsman Speaks

What music first inspired you?

Well, in 1966 there was so much going on, and you only got to hear it because pirate radio played it — the BBC didn't. You'd have a transistor radio and listen to it under the bed when your parents thought you were asleep. It was bands like the Small Faces, the Rolling Stones, the Equals, the Amen Corner, the Kinks — all these beat groups. But the Beatles were the biggest influence on me to play guitar. To me it's the most important music ever made. I'd taken the obligatory piano lessons at my parents' insistence. One month after I bought my first electric guitar, I was fired by my keyboard tutor for not practicing, which was inevitable.

I met Andy in 1969 for the first time. I had a group called the Pink Warmth. We played at the local youth club on the Penhill Estate where Andy and Colin Moulding grew up. I remember meeting Andy there, and I used to bump into him on Saturday afternoons when we'd all go around to local music stores. The proprietors would hang the Fenders high on the wall so that eager young hands couldn't touch them. But occasionally you might be able to get one off the wall and plug it in. They'd quake in their shoes when they saw us coming because they knew they were in for a noisy Saturday afternoon.

What were the circumstances of your joining XTC?

It was always Andy, Colin, Terry Chambers, and a keyboard player. Barry Andrews quit at the end of '78 — he was at odds with Andy telling him what to do. I assumed they'd look for another keyboard player, but Andy called from Boston and said, “Barry is quitting. We must have a meeting when we get back to England.” At that time I was delivering parcels, so I was more than happy to take his offer! At first I was attempting to copy Barry's keyboard style with my guitar, but Andy said, “Forget Barry. Let's reinvent the band. From now on we are a guitar band.”

The new album is great. How do you feel about it?

It's my favorite to date. It's got the right combination of great songs, great production, and competent musicianship. We're very pleased with it. The guitar solo on “That Wave” didn't come easily. It's over a very strange Gm6 sort of chord. I took a couple of stabs at improvising it, but Andy said, “Do you mind doing it again?” It was decided that I would overdub it the day of the mix. I'm very proud of that solo, and I'm glad Andy made me do it again. It plunges down to the bottom of the sea and climbs out again like a marlin rising out of the surf. [Laughs.] It covered the entire length of the fretboard, from a low F to a high D.

On “Humble Daisy” and the lead lines to “The Ballad Of Peter Pumpkinhead,” I was going for a sound between Neil Young's “Ohio” and the lead lines from “And Your Bird Can Sing.” On the very last chord I hit a big D, and I tuned down the low E so it would resolve to a D also.

I'm glad we could have a bit of real rock and roll guitar at the end of “Books Are Burning.” The original plan was a “Hey Jude”-style na-na-na chorus. I said, “Let's have a guitar battle just for the crack. What better way to finish the album?” Andy was suspicious, but we twisted his arm. I think it stopped just this side of good taste. We soloed over G-D7/F#-E7/G#-Am-D7.

What is it like working with Andy?

If push comes to shove, it must be done Andy's way. I've learned to live with it, and it usually bears fruit. Andy always knows what he wants — there are never any gray areas. But occasionally the fur does fly.

He's never played guitar to any rules. That's the way he does everything

— and he always gets away with it! He can just throw his hands on the

guitar and before you know it a complete song has materialized. It's quite

uncanny, and most unfair. He's still very wary of doing gigs, but there's

nothing he likes more than an audience. Get a few people in a room, and you

soon find out who the center of attraction is. He's a natural

entertainer. Maybe he's just shy, and there's some thing inside him that doubts

how entertaining he really is. He's had a lot of bad luck with management and

money and the rest of the lot. It's really a triumph of artistic skill over

adversity. The thing that kept us going was that he kept writing songs. That's

what it's all about: sheer song power. ![]()

Go back to Chalkhills Articles.

[Thanks to Graeme Wong See and David Oh]