by Art Dudley

A Chalkhills Exclusive (a shorter version of this interview was published in Listener magazine).

XTC first came to the public's attention in the late 70s, after signing with Virgin Records. Their first albums were quirky and energetic enough that XTC fit in well with the punk movement. But it became clear early on that there was more to them than mere thrash - and that of all of the bands to emerge from post-Pistols England, this one would endure.

A couple of decades later, XTC continue to make wildly original pop music - albeit on their own terms. Early in the 80s, after a succession of grinding tours, songwriter and group leader Andy Partridge suffered a near-total breakdown, and XTC ceased all live performing. Not long after, drummer Terry Chambers went his separate way, leaving the band to carry on with various guest percussionists - all the more cementing their status as a recording act.

XTC have now started their own label, Idea Records, which is distributed in the US by TVT Records. (Visit them at www.tvtrecords.com.) As this was being written, Idea/TVT had just released a box set of XTC's BBC recordings titled Transistor Blast, and were making plans for the early-1999 release of the group's first collection of new songs in years.

Andy Partridge, a man funny enough to do standup comedy should he ever tire of pop music, spoke with us about all things XTC - including their new book, XTC: Song Stories, written with Neville Farmer and published by Hyperion.

Listener: So you're an author now. Congratulations!

Partridge: Well I don't know about "author." I feel much more like the subject of it than the actual author. It's a bit like talking to Joe Stalin because there's a book about Joe Stalin, if you know what I mean. "Oh, Joe, you're an author!" [affecting comic Russian accent:] "No, no! I was merely subject!"

Listener: [laughs] Okay, yes that does put in into perspective. Now before moving on to the lesser questions, let's get the most important ones right up at the top. Who is your favorite Spice Girl?

Partridge: Oh, definitely Gerry.

Listener: Ahhh...

Partridge: She was the reason that any male--

Listener: Any real male--

Partridge: Any real, hot-blooded male would even look at the Spice Girls. And everyone knew she was in her mid-thirties. That twenty-five nonsense, that wasn't washing with anyone.

Listener: No, and that was the appeal too.

Partridge: That was the appeal, yes: the fact that she was a lying little ginger-haired minx...

Listener: [laughs]

Partridge: She had a twenty-five year old tongue and thirty-five year old neck. [laughs] You know, you just can't hide those necks. [laughs] No, she was my favorite two reasons for looking at the Spice Girls.

Listener: Okay, that makes perfect sense. Next: Which one is your favorite Teletubbie?

Partridge: I detest them!

Listener: Really?

Partridge: I detest them! I mean, for God's sake: a bunch of animated, gibberish-talking fluorescent socks that live on a golf course! [laughs] Yeah, actually, I would love to see, like, a wild boar come over and occasionally just knock one down. Club one to death. [laughs] You're watching the little bunny there, and then this boar comes hurtling, supersonically, out of the blue, and--THWACK!

If I were four years old, I'd be in love with the Teletubbies, but there's something about them that rubs me up the wrong way. I like the sun, though, actually--the kid who plays the sun...

Listener: He's got a lot of teeth for a kid his age, though, doesn't he? Otherwise I'd take him to be about one-and-a-half, thereabouts.

Partridge: I think he's about forty-eight years, actually--

Listener: Drug casualty?

Partridge: [laughs] Dribbling away in the clinic as they close in on his face! Exactly -- he's older than you. I think he was the kid on the front of the Bangladesh Album...just got a lot older.

Listener: Yes--"Where are they now...?"

Partridge: Where are they now? They have an "Indie" band of their own, I'm sure.

Listener: [laughs] No pun intended, I'm sure.

Partridge: No pun intended, none taken. [laughs]

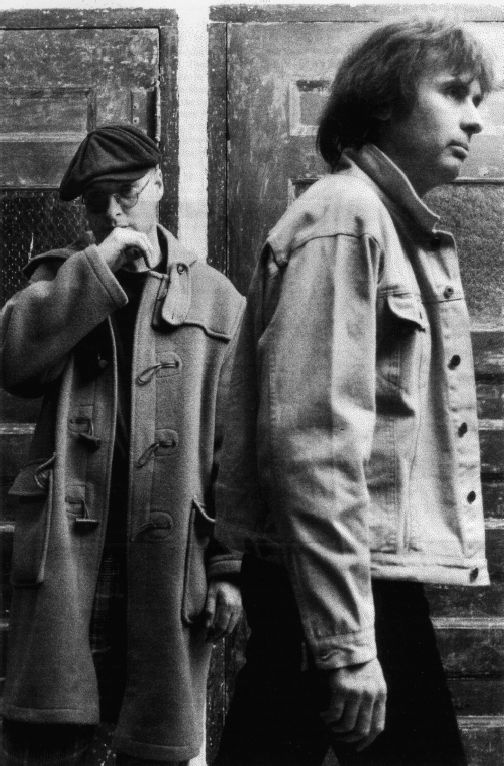

Colin Moulding (left) and

Andy Partridge, soldiering

on as a two-piece. . .Listener: So back to the book, which I have to admit I just finished reading last night, just under the wire.

Partridge: It's not my favorite thing, that book.

Listener: Really?

Partridge: I have funny reservations about this book.

Listener: No kidding! would you prefer not to talk about it?

Partridge: Oh, no. I mean, I'm the best torture victim in the world: I'll tell everything!

First of all...because I'm one of subjects of the book, it's tricky for me to read some of that stuff. And we also gave Neville Farmer a free hand to write what he wanted, and I think it's a little sarcastic in places--which I think is partly Neville's, umm, personality...

Partly because Neville's been on the periphery of the band for many years now, I also think there's a little dollop of jealousy in there. And also because we agreed that we would let it be his opinion, his write-up, his baby--well, we saw some of his stuff in rough drafts, and we were reading it and going, "Oh, I don't like it there, I wish he hadn't said that!" Or, "Ouch! Why did he say that?" But we decided to leave all that stuff in, because--well, that's what makes it his warts or our warts or somebody's warts in all.

There's lots of things. There's also the fact that Hyperion reduced him to something like three hundred words, on average, per song--and honestly, in my opinion, you could easily write ten thousand words on each song. We gave him ten thousand words or more on each song in the interviews, but he was reduced to having to hack it down to an average of three hundred, so some songs got a couple of lines and some got a bit more than three hundred, you know....

It's okay. It's an okay book. It's a pop book: What can I say?

Listener: Yeah, but he's obviously a fan, and he admits that right up front.

Partridge: Yeah, he's obviously a fan, but it's--Oh, I don't know. I come over particularly badly for some reason--like, I come off as a little brain-dead when I'm reading this thing. I just wish he hadn't picked all the swear-y quotes, 'cause I can't let my parents read it. [laughs]

Listener: [laughs] Well, you didn't come across that way to me...

Partridge: Maybe it's just because I feel a certain way about the band, and I don't think that has totally come across. But then again, I'm not the only person in the band--and anyway, it's Neville's book, basically. It's largely his take on things, interspersed with opinions drawn from interviews with us. Which are heavily edited.

I think, actually, where he lets us talk unedited, it's quite funny. But, otherwise, where he pulls out just bits and pieces, they seem a little disconnected in some way. But it's okay, it's an okay book. Did you enjoy it?

Listener: I did, very much. The things that were most surprising to me had to do with your own attitude toward the band, and toward your fans. For instance: I'm fairly new to the Internet, and I didn't realize that there were so many fans out there who were communicating with you that way--

Partridge: It's a frightening amount.

Listener: And I suppose that's good, but--

Partridge: It's a little obsessive. I'm not on the Internet myself, but I've seen some of that stuff occasionally, and it sort of frightens me a little.

Listener: I can imagine it would. That kind of fascination with a band is--well, I'm an XTC fan even though I'm trying very, very hard not to gush...

Partridge: That's okay; my "shucks" button is broken at the moment [laughs].

Listener: [laughs] When you like a band this much, it's understandable to care about them and to want to learn about them. You hope they're sleeping well and getting enough to eat and all that. But there's a limit to it, you know? There's a limit beyond which sane people don't go because that would just be--weird.

Partridge: Yes, but some people do. Some people go way beyond that limit. It's amazing, the stuff they talk about. I've seen a tiny tip of the iceberg--not even that--of some of the stuff they talk about...

The real hyperbole, I don't believe. Because--it's just me! And I fart like everyone else. [laughs] I get spots and I'm lazy and I'm just a normal schmoe. [laughs] So the hyperbole I don't believe, and then the real hurtful stuff--you know, the stuff like, "Oh, this record is just crap compared to such-and-such-and-such-and-such, and when you hear these songs, it's obviously a once-great man falling apart before your very eyes, it's so sad to see this"--I'm destroyed by that!

So I don't believe the hyperbole, and I don't want to believe the heavily critical stuff. So the Internet for me, all the different sites--well, talk about a misinformation highway...

Listener: Now, getting back to Neville, when you say the book presents a sarcastic attitude toward the band...

Partridge: I don't mean this as a slap in the face to Neville, 'cause I think he did a pretty good job. But I think Neville's personality is that--he is very English, and the English like to cut everyone down to size. And they do like sarcasm, and that's possibly the only part of me that isn't very English, because I detest sarcasm.

Listener: Yes, that came out when I read of your experiences making the Skylarking album with Todd Rundgren, who I gather can be very unpleasant.

Partridge: Yes, and that's how he is very un-American: He's extremely sarcastic. I don't think of the Americans as being sarcastic.

Listener: No, I don't think so as a rule.

Partridge: No, I don't think Americans are sarcastic, and I don't think they have much of a sense of irony.

Listener: No [laughs], that's a very safe thing to say.

Partridge: Well, generally, the only ironic thing the Americans have done or the only sense of irony they've ever displayed is in Wayne's World, adding the phrase NOT! to the English language. [laughs] You know, so-and-so-and-so-and-so-and-so-and-so-and-NOT! That's America's contribution to irony.

Listener: I'm sensitive to sarcasm, and I was shocked to hear how difficult Rundgren was...

Partridge: I've said a lot of...well, I suppose they're truthful, but I have said a lot about Todd in the past, a lot of hurtful things. And I don't want to keep turning the knife. He did a fantastic job.

Listener: It's a brilliant album.

Partridge: He did a great job. He really did a good job in the way that he took all the material we gave him, sorted out about half to two-thirds of it, and organized it so that it seemed to flow together. Basically he chopped the demos together, the cassette demos, and edited them--so he'd already made the album in cassette form!

Listener: When I first heard it--well, I didn't have any idea how much involvement Rundgren had: Obviously, "producer" means different things given different projects and different bands.

Partridge: Of course.

Listener: But I imagined that the song ordering surely would have been determined by the band.

Partridge: Well, it usually is. We were less involved than that because, to a large extent and apart from a few tweaks, even before we'd spoken to him on the phone, he had all of our demos and had edited them together. He'd taken verses out, choruses out, moved stuff around. He had done most of this kind of work that we do for ourselves normally--he'd done the most of this that anyone has ever done. But he did a very good job of it, and that wasn't my problem. His sense of arrangement was fantastic, that wasn't a problem. It was his--and many people have said this, but unfortunately I hadn't heard them say it until after we'd worked with him--he's very very difficult to be with on a personal level. He...he likes to break you, so that you'll say, "Well, anything you want to do, Todd, it's not a problem."

Listener: Reading about him in the older XTC book--was that Chris Tomey or Toomey?

Partridge: "Do-me Twomey" [laughs]

Listener: [laughs] Well, I'll never forget that, will I?

Partridge: [deadpans] "The fun-loving Chris Twomey." [laughs] Poor old Chris: He's not the happiest of people.

Listener: Todd came across in both books and in other interviews I've read as just a bit sad. Have you ever spoken to him since you wrapped up that record?

Partridge: No, but I've seen some interviews from TV, where he's obviously defending himself, because he's--I suppose rightly--been hurt by some of the things I've said. But, most people tended to go for the hurtful things, whereas I think, in balance, he did do a great job. And if it hadn't have been for the fact that I personally did not get on with him nor him with me, I would have loved to have work with him again. He was very sympathetic to what we wanted to do.

Listener: But you would rule that out now?

Partridge: I think so. I just think it would open up too many old, festering sores, you know? We were just two very headstrong people that wanted to do things their way, and I think I felt extra wounded by being obliged by the record company to toe the line. You know: [affecting a pained artist's voice] "Because my vision had failed...!" [laughs]

Listener: [laughs] Now, I want to pick up at the ending of your book, because it's a real cliffhanger. You've written and recorded these twenty-some-odd new songs and you've got a whole new musical direction with your orchestral material, and you've got a new record label...

And yet, Dave Gregory has left the band!

Partridge: Mmm, it's a bit of a sting in the tail at the end there!

Listener: So what have we missed since then?

Partridge: Well, Dave left halfway through the making of the record. There are a million and one reasons why Dave left; let me try and corral some of these together for you...

Dave is a diabetic and has enormous mood swings, which are very tricky to work with. Both Colin and myself--well, in fact, other people in the band as well and other producers and engineers--have found it very difficult to work with Dave. Like, one moment he's Mister Positive and up about something, and it's the best thing you've ever done! And then the chemicals will kick in or whatever, and he gets extremely depressed, and it's all shit and he doesn't want to continue and it's not worth doing and all this kind of thing.

So when you work with Dave, your emotions get pulled along on this rollercoaster with him--which is very difficult to take, because you don't quite know if he's liking something or hating something. Is it chemical or is it Dave? In fact, he gets so insulting sometimes and so negative about things because of his condition, that Colin and I coined the phrase "adding insulin to injury." [Andy and Art pause for a good laugh at that] It's just so very difficult to deal with, you really don't know where you stand.

Listener: He's very negative in some portions of the book, talking about certain songs...

Partridge: Well, he didn't even want to contribute to that book. It was only Neville, pestering and pestering...

And in fact Colin and I got together with Neville and did dozens of interviews. And after a hell of a lot of pestering, Neville only managed to corner Dave once. In a telephone conversation. Which he had to splice in.

Listener: Oh...

Partridge: He told Dave what we were talking about and said, "What would be your comment on this?" And Dave reluctantly gave him something like an hour on the phone.

So he didn't want to be part of the book. He didn't want to be part of making an orchestral record, because he's a guitar player and he doesn't want other people playing what he sees as his music. He was angry at me because he doesn't write songs, and there's a lot of resentment been building up over the years, Dave being a translator and not an originator--and whose baby is it, is it the translator's baby at the end? Or is it the originator's baby at the end? He's very angry that we don't tour...

I mean, these are just some of the major issues. There's millions of minor ones as well. And looking back on it now, it seems plain that over the period that we were on strike and in the fridge and storing up stuff for the new record, I can see Dave trying to extricate himself in subtle ways from the band, which really came to a head during the making of this record. And he left about halfway through. And Colin and I finished it off ourselves with Nick Davis.

In fact, what happened is that there's a very bizarre shape to this album, in terms of recording. Because the other two reluctantly agreed to go along with my concept of doing a double-pack CD, of the twenty-two best numbers. These are best in democratic terms that is: We took everyone's considerations and we have a voting system, and so it's "the best" democratically, really...

We picked the best twenty-two songs out of forty-two and I said I'd really like to do this as a double-pack: One of the discs would be all the acoustic/orchestral material. And the other disc would be all the more up-front, more idiot kind of electric stuff. Which, yeah, it's a side of me I have. [laughs] A reasonably complex side and I have a really idiot side. And I like to indulge both, if possible.

So we picked Haydn Bendall, who has a great background in engineering from Abbey Road--he's been there forever and he's done so many sessions with so many people. And everyone was saying, "Oh, if you're gonna work with orchestras, you should really work with Haydn, he's got a great ear for orchestra recording and he's great with editing and stuff like that." So we started with Haydn, really on a programming kind of front, because we wanted to map out the whole record--so we knew what we were doing when it came to recording the orchestra. Just yawn violently if this gets boring...

Listener: [laughs] No--

Partridge: We started, with Haydn, mapping out. We had a terrible hiccup where we were supposed to be using Chris Difford's studio down in Kent, and things went terribly wrong there. Basically, his studio wouldn't function properly. It caused us a lot of wasted time and money.

Listener: Did you still have to pay for it?

Partridge: Well, we were led to believe that because we had so many problems there, it was free. We didn't expect to pay for it--and then he hit us with a bill, and I got very upset and left the studio, and said I didn't want to work. I didn't want to pay for anymore "free" time. And then--he stole our tapes. So we had to start the album again. So Chris Difford still has the original tapes.

Listener: You're kidding?

Partridge: No, no, not at all. He's never let us have them back.

So we started again in January at Chipping Norton Studios. We mapped out a load of stuff--the same stuff again, with sequencers and guide vocals, you know, just sketching--and we recorded some live drums and piano and basically any of the live-sounding things, the things that needed a lot of good space around them, mostly percussive things. And during this time I had a few big rows with Dave. Things weren't going too great.

Then we went back to Haydn's to edit what we'd recorded. And I said that, because of the speed at which Haydn was working, and because of our budget, we were not going to get all twenty-one songs recorded. So I said, why don't we just concentrate of the orchestral, acoustic stuff--

Listener: And do the electric stuff--

Partridge: And then do the electric stuff a little later. Dave didn't like that suggestion.

Listener: Well, he would have less to do on the orchestral material...

Partridge: Exactly. He felt snubbed in some way. But, you know, we had long arguments about this in which I said, "Look, I'm hardly on this record at all. I can't play viola, Dave, or violin, or bassoon, or drums, or--do you see what I mean?" And we decided--well, Colin and I decided, Dave was much upset about this--to work on the orchestral/acoustic side of things. And then we booked an orchestral session at Abbey Road, with a forty-piece orchestra. And Dave threw up his arms in horror and left the band before this--a couple of weeks before this happened.

Listener: Oh, dear.

Partridge: He didn't want to spend the money on the orchestra. Basically, he said, "Well, why can't we just do it with synthesizers?" I said, "It's not going to sound the same!" It doesn't have the passion and the power of a real orchestra, you know!

And Dave threw his arms up and left. And although we plotted out and recorded some bits of the album, over X amount of months, we actually recorded most of it in one day--at Abbey Road! With the orchestra!

Listener: Now, do you add to that any of the things that you had already recorded in Chipping Norton Studios?

Partridge: Sure. We had live drums on stuff, we had live piano on stuff, a few acoustic instruments, bits and pieces.

So, we put the orchestra to the tracks where we needed them. And we recorded, actually, the majority of the sounds in one day.

Listener: That's remarkable!

Partridge: It's remarkable, just because of we spent months plotting this out. And we had a false start at Chris Difford's.

Then we spent a couple of months--you see, because we had to slam this stuff down really quickly with the orchestra, and because the nature of orchestral recording is all in editing--we spent literally a couple of months editing the orchestra. But then Haydn, who's a great chap to work, but he's so painstaking that we literally ran out of time with him, had other projects he was contracted to do, to work with Peter Greenaway and various other people. Haydn said, "I'm really upset that I can't finish this album off..."

I panicked and ran and called Nick Davis. I thought, well, Jesus, we're gonna need a great engineer to finish this record. We've run out of money, I don't know where we're gonna record it. But I rang Nick Davis. And he said he was free--he'd just finished a project.

And Haydn said, "Well, look, why don't you buy a few bare essentials and record it at home?" So we bought a great quality microphone, a reasonable quality mixing desk, a couple of great quality valve compressor/limiter things, and we took over the front of Colin's house [laughs] and spent the next the next couple of months in there, recording, you know, acoustic guitars, all the voices basically, bass guitar...

So that long, boring, dribbly conversation I just did was trying to put in a nutshell the recording process of this album!

Listener: So Dave is presumably on a lot of the tracks that you recorded at Chipping Norton Studios--pianos and guitars and the like?

Partridge: He's a reluctant keyboard player. He's pretty good. But, he's reluctant to do it, because he sees himself as a guitar player.

Listener: I think he's good on keyboards because he's not too good.

Partridge: Yes, he's good because he doesn't overfrill. So he plays piano on "Harvest Festival." He plays piano on "Your Dictionary." Umm, what else is he playing on? He's not on too much, because he left before we got a lot of his contributions recorded. And so consequently Haydn had to play a couple of keyboard things, and Nick Davis had to fill in a play a couple of keyboard things.

Listener: And you play keyboards a little, don't you?

Partridge: I haven't done on this album. I mean, I've done stuff in the past, just odd little bits and pieces. But it's nothing more than one-fingered. I'm just so slow at keyboards. I can work at home, composing with a sequencer a note at a time, you know? But, in the studio it's just too expensive to do it that way.

Listener: Now you've mentioned a couple of the new songs from the forthcoming album. And there's one that I've read about already: People on the Internet have been talking a lot about a new song of yours called "River of Orchids." And I don't mean to be glib when I say, I think it's my favorite song that I've never heard--

Partridge: [laughs]

Listener: To hear it described, it sounds amazing...

Partridge: Have you heard the demos?

Listener: No.

Partridge: Because everyone that contacts me says, "I have all the demos for your album!" [laughs]

Listener: No, I haven't heard any of them. I feel so left out.

Partridge: Well, how can I describe it? I hope it's not going to take any value away from it, if I tell you how I found it. But, at the end of Nonsuch, I really wanted to do a record with orchestral textures. I mean, you can see that coming, I think, with stuff like "Wrapped in Grey," "Rook," "Bungalow" to some extent, "Omnibus," and maybe "Humble Daisy." You know--stuff that doesn't sound like rock and roll stuff.

And I really wanted to do a record with those kind of sounds on. And I bought myself a sampler with a lot of orchestral samples. And the first stuff that was written immediately after Nonsuch tended all to--well, I wanted that flavor for it, I wanted orchestral textures.

And I was messing around with samples of plucked strings one day, and I found a two-bar section where I thought all of the parts rolled together very well and counterpointed each other, so they were in constant conversation. And it was just plucked strings and trumpets...basically a two-bar loop of this.

So I thought: This is so infectious! I mean I was literally dancing around my little home studio for hours to this thing going round and round and round. I didn't know what to do with it. But I just loved the sound of it! I thought, this is incredibly inspirational, and I couldn't believe that I'd actually constructed this. You know, a case of really surprising yourself. I'd made something that was--that really surprised me and delighted me. And I hadn't quite figured out how I'd done it. But, I'd done it a note at a time, and it was really working. And I was just dancing around, singing stuff off the top of my head.

I was looking through my lyric book, and I had a line which I really liked, which was, "I heard the dandelions roar in Picadilly Circus." At one time it was going to be an album title, it was one of the potential album titles for Nonsuch. But it was a little bit too long.

And I was singing this line to this, this looped, little orchestral thing, and just improvising this line and improvising other words as well. Almost immediately a song came out. A very simplistic song, almost like a nursery rhyme. And I found other simplistic songs--it was very easy to improvise over this orchestral loop. And I picked out the best three tunes and made them work together so that you could sing them together, they would cascade over each other, they would respond--you know, "Tune Two" would respond to "Tune One," and "Tune Three" would come in and complement the other two, and so on and so on. So it's almost like three little nursery rhyme tunes that you can fit together. And it goes over this unchanging music for about six minutes.

And we agreed to do this with a real orchestra. And we scored out an intro where the orchestra plays just one pluck--each instrument would play one pluck, and then two plucks...and it would slowly add, like drops of water, until it forms a torrent--which becomes this orchestral loop. And at the end, the nursery rhymes shift in over the top, commenting on each other.

Listener: It sounds gorgeous. And this is the one that's going to open the orchestral album?

Partridge: Yeah. It starts with a drip of water which is then answered by plucked strings. And then another drip, and then two more plucks and then another drip, and a couple more, until you get this torrent that becomes--you slowly get to hear the rhythm of the track built up. [laughs] It came out pretty well!

Listener: I'm so looking forward to hearing it.

Partridge: If I sound really stupid describing it--well, when you hear it, you'll say, "Ah-ha, I see what he's saying..."

Listener: I really can't wait to hear it. When is it coming out over here, do you know?

Partridge: At the moment, it's the second week in February.

Listener: And the title? I had heard, at first, A History of the Middle Ages was tossed about...

Partridge: That was what I wanted to call it. Because I thought that was very truthful, we're all middle-aged men. And this, all this material was written over the last four or five years--and so it was a history of our middle ages, and all the things we'd been through.

But Dave Gregory hated it so much, and we had this argument where he insisted--he's the oldest member of the band, or was the oldest member of the band, and he was vehement that he was not middle-aged. I said, "Well, look, you know, as far as I'm concerned, when you hit thirty-five you're middle-aged. You aren't going to live much past seventy-something." And he said, "I do not want you calling it this. I do not want people thinking I'm a middle-aged man."

I said, "Well, for Christ's sake, you are. You know, you're graying, you're balding, you're the same as us." You know, we're graying and balding! We're paunchy! We're middle-aged men, for God's sake! And he couldn't accept this. It's one of Dave's problems. I think he's--God this is gonna sound so critical, but, now that I've started, I'd better finish the sentence--I think he's a little stuck. Because his diabetes hit him in his teens. And I think he resents missing a lot of the normal things in life, and is hyper-conscious of aging. And so me wanting to call the album A History of the Middle Ages really upset him.

Listener: I can understand that now. Have you two been able to be friends at all since then?

Partridge: Not at all. He hasn't spoken to me since March.

Listener: And you still both live in Swindon, so presumably you're not that far from one another.

Partridge: A couple of miles. But I haven't bumped into him. I used to bump into him a lot. But I haven't bumped into him. And he hasn't called me. I've got drunk a couple of times and considered calling him--drunk. But, thankfully, Art, I sobered up enough to think, No, this is crazy.

So that was what is was going to be titled. Then it was changed to Apple Venus--which is just something I felt suited the kind of Pagan feel of a lot of the music.

Listener: And there have been a lot of Pagan references in a lot of your songs since--well, since English Settlement...

Partridge: Sure. Oh, Colin and I were talking recently. We were messing around with the phrase "indoor boys and outdoor boys." You know, about sort of delicate kids and rough kids. And we were talking about "indoor songs and outdoor songs." And we came to the conclusion, that on this album or certainly on the last few albums, Colin writes indoor songs. About indoor subjects. And I write outdoor songs, about outdoor subjects.

And yet he's more of an outdoor person and I'm more of indoor person! Maybe we're hankering after something that we're not, in our songs...

Listener: Apple Venus is from a line in your song "Then She Appeared," right?

Partridge: That's right. All of our fans are besotted with the idea that our titles of our albums come from previous lyrics--but that's not true.

But this time I thought I'd take the suggestion and look at some past lyrics. And I quite like the phrase Apple Venus. I thought, well, why not carry that on?

Listener: It's nice, evocative little phrase. It just has a nice feel.

Partridge: That seems to be the flavor of the music on this record. And Colin was happy with that, you know. He didn't hold his hands up in horror and say, "No, this doesn't feel right!" So the ones that don't get protested about, they're the kind of ideas that go forward, you know.

Listener: Do you listen to a lot of classical music yourself?

Partridge: Not a great deal, I don't listen to that much music. I know it sounds a bit moronic, but..

Listener: Not at all. I mean, I would think it would interfere to some extent with your writing: How can you think about your own music if you're hearing a lot of other music?

Partridge: Yes, kind of. I think it interferes with getting music out. Putting music in is one thing, and getting it out is a total different thing. You have to have a totally different "organ" for getting music out.

Listener: Now that we're into the territory of your own listening habits, let's bring up the fact that a lot of your albums have sounded really great. English Settlement, I think, and Black Sea really jump out of the speakers. And you and Colin make some references to that in the new book, about how songs like "Towers of London" sounded go good on playback. Was this something that's been driven by you, or is it just good fortune that you've been well served by your engineers and your studios?

Partridge: I just think we've been lucky, literally from day one, to have people that know what they're doing. And...I mean, I think our albums sound okay, but I think other people's records sometimes sound better in quality than ours. And sometimes people achieve things where I think, How the hell did they do that?--in terms of sound quality. How do you get that sort of quality? I mean some of the Michael Jackson records: His music gives me the willies [laughs]. And he is a person who I think is in need of assistance. He needs help, that boy. But his records sound so three-dimensional. And I suppose it's the people, and the money spent. You can hear it, you know. Or Blue Nile, whose records always sound very three-dimensional to me.

Listener: Sometimes, though, it seems to be opposite to the application of money or technology, because some of the best sounding records are the simplest--where somebody, you know, throws up a couple of microphones and says, let's just do it.

Partridge: Sure--well, there seems to be a direct corelation between the amount of instruments recorded and the perception of volume and "magnificence." And I find that the least instruments recorded always sound louder and more present, and you're able to get your head inside them.

Listener: You can hear the air around them.

Partridge: Yeah, and then the more instruments, they crowd onto tape, or they crowd onto the media, and they sound farther removed. So in that case--a lot of this album, apart from a couple of tracks, a lot of this album sounds farther away. Because we're dealing with in some cases a forty-piece orchestra, and in some cases it's been overdubbed to form an eighty-piece orchestra, and overdubbed again...

Listener: Do you have any personal feelings regarding digital recording versus analog recording--or for that matter, regarding CD versus LP?

Partridge: Sure. I don't know if they would be the same as other people's opinions. But I prefer the sound of vinyl. I prefer analog recording. But I don't like hiss. So if somebody's going to invent --eventually they will--if somebody invents a digital format that sounds just like great quality tape, that would be ideal. But nobody's quite done it yet. They're getting close, but it still doesn't have the sort of "love" that analog puts there...

Listener: Yes, that nice organic quality.

Partridge: Sure! Digital doesn't have this kind of "home love" that analog puts onto the music. But, you know, you can do without this fact that, every time you run it over the heads, it wipes some of the music off, wipes the highs off. It gets rid of the oxide, you know, it hisses. You can do without all that. Because each time you play an analog recording, you're degrading it.

Listener: I think probably Nonsuch was the first XTC album that I couldn't find on vinyl: I had to go out and buy it on CD.

Partridge: It's there--it is on vinyl.

Listener: Actually, it's one of my three or four favorite XTC records. It's held up very well.

Partridge: Good man! Because I've had a lot of flak. You know, people have written to me, or I've seen stuff on the Internet--obviously, I don't have the Internet, but, people occasionally post me bits and pieces--and they say, "Oh it's my least favorite XTC album. It's too safe. And it's all these kinds of things..." And I think, fuck you! [laughs] It's one of my favorites! [laughs]

Listener: Oh absolutely. It's got a big chunky feel to it. The songs are very substantial--there's a lot of heart in every song on the record. There's nothing glib or cold about it. I love it!

Partridge: Yeah, well, I think you're in a minority. I think a lot of people that like us prefer things like, Skylarking, English Settlement, and Oranges and Lemons. Those three. Some of my favorites are Big Express--

Listener: I've just found myself going back to that one over the past couple of months. When it first came out, I liked it, but it was more "angular" than the albums that preceded it immediately. English Settlement and Mummer were--

Partridge: They were a little softer.

Listener: Yeah. And The Big Express was harder, and it was a little more challenging--like the horns on "Seagulls Screaming, Kiss Her, Kiss Her." I didn't get it at first.

Partridge: Well, you see, you think they're playing like the wrong tune or something. That was a little abrasion I had with Dave, about what the horns are playing over the chords. He said, "They don't fit." And I said, "I know they don't!" [laughs] But it had the right effect on him after, this slightly dreamlike, alienating feel where you can't quite believe what you're hearing, just as you can't quite believe what you're seeing when you stand on a foggy Winter beach.

Listener: It was very effective. It really caught that.

Partridge: Well, I really had to fight for that one. Both he and [producer] David Lord wanted to change it so it sounded much sweeter to the ear.

Listener: I'm glad you didn't.

Partridge: I stamped my little cloven hoof to get my way with that!

Listener: [laughs] Well, you got your way.

Partridge: Just. I like cheery music. But "Seagulls..."--you can go back to it. There's marrow in them there bones.

Listener: I know you don't take yourself too seriously, and I know you don't want people to take your songs too awfully seriously--

Partridge: No, it's just music--

Listener: But, if there were one or perhaps a few of your songs that you wish people really would take to heart, which ones would they be?

Partridge: That's a tricky one. That's a tricky one to answer because I wouldn't want to come off as preachy. And if I thought that a song had a message, I'd hate to push that message to the front, because it might get under the magnifying glass and people might think, Hmm, that's perhaps a little preachy." And then again, I wouldn't want to push, say, a trivial one to the front, where people would think, "Hmm, he's just an empty-head."

Some of the songs have affected me, have caught me at side-swipes that I never thought they were going to. Some of them because of the sound of them--you find a certain chord change or a certain phrase, and you're tripped up emotionally, and you think, Oh My God, Where did that come from? "Rook" was a great example of the that. That really scared the shit out of me. I don't know where that came from.

Listener: It's very--I can't even find the words to describe it. It's not dark, per se. It's not a dark point of view. But, it is a little bit scary.

Partridge: A little bit scary, and I don't know why.

Listener: It's almost like sitting around and trying to scare yourself--to think, Well, do I have a soul?

Partridge: Do I have a soul? And it's also the closest--it's one of the closest I've got to singing a dream, if you see what I mean. Singing something where you translate your dream time into real time. But I wouldn't want to push that to the front--because now people would start leaning on that. It may crumble a little if they start to lean on it.

But that one affected me. And "This World Over" affected me because of the chord change. I just found it a very emotive chord change. But there are other songs, too, you know--things I'm proud of. It's almost like a kid being proud of, you know, being able to do his alphabet or something. I'm very proud of "Seagulls Screaming, Kiss Her Kiss Her." It was the first song I ever wrote on the keyboard. And it's like when the kid learns to whistle or ride a bike or whatever! You never forget those little sort of achievement things.

What else? "Books Are Burning"--just because it was a song where I felt as if I was really standing up to protect the book in some way. And I don't know what the hell that means. [laughs] There's something about books, I just love books. And if they contain the wickedest ideas in the world, then so be it. There's license for them to do that. That's one of the few forums that you should be allowed to put your soul into--your heart and soul into. And so I think destroying books is the same as destroying people, because books are repositories of the the soul, if you see what I mean.

But, yes, I was proud of that for that reason. Different things for different reasons--and not necessarily the successful ones. Like I don't think that "Senses Working Overtime," our biggest success in England, is necessarily one of our best songs. I'm more proud of something like "Mermaid Smiled," because I think I got close to capturing something that I found magical as a kid.

I wouldn't want to push any of these songs really to the front. Because people are going to lean on them and they're gonna bust. I'm proud of them all and not proud of them all--as in, you have to get them out of the way and move on. I don't want to go back and say, [affects effete voice] "And here, this room contains all of the songs..." [laughs] You know? I wouldn't want to do that.

Listener: Let's talk for a moment about the new box set, Transistor Blast.

Partridge: Half the set is live recordings, from very early on--so it's very young and aggressive and rather naive. And the other half are BBC sessions, studio sessions, done for various deejays, such as John Peel, Kit Jensen, whoever was commissioning sessions at that time. And those sessions are done in a BBC studio, and you put yourself in there and do them very quickly in an afternoon. And so you basically get to play the track live, and then you may get one overdub, or time for one overdub and maybe to put the vocal on. And that's it.

So, they're more stripped-down versions. That doesn't mean to say they're bad: Some of them are more in touch with the nature of a song, because you can't futz with them and, you know, you have to slam them down very quickly. So the studio sessions are between '77 and '89. And the live stuff was done specifically for the BBC--from '78 to, I think, '81.

Listener: Is this material that you have had access to yourself over the years?

Partridge: No, the BBC owns the copyright to them. I heard most of this stuff for the first time in 20 years. And I was petrified--that it was going to be so naive and so sort of gangly and stupid...

But I was delighted, actually. I laughed my socks off when I heard it. I mean, it's extremely mannered, and it's rather like naive art--you know, we didn't know what the hell we were doing, but it's nicely finished. Like great naive paintings or something: They haven't grasped perspective and they haven't grasped proportion. But they finish off very nicely and that's the best they can do. And that was like us at the time. You know, we were very young. We weren't great at songwriting. But there was a great energy and a real vivacity to it, and it's finished off nicely and we try and put the whole thing together. It does have a really appealing naivete. I did laugh my socks off when hearing it. I thought, My God, the sauce of these young kids! Because it really is a different "me" making that music.

Listener: Is [departed bandmate] Barry Andrews on these tracks?

Partridge: Yeah, he's on one of the live albums. In fact, one of them is his very last gig with us--which I didn't know at the time, but I sensed that was the case! And he's on some of the session stuff as well.

Listener: Are you still friendly with him?

Partridge: I see him occasionally--not intentionally. We end up bumping in to each other, or he'll call me for one reason or another. But, we must speak about once a year. And he always looks distressingly healthy for a man who I know wrecks himself! [laughs] He doesn't make music anymore.

Listener: Really?

Partridge: He welds. He welds metal together. I mean, some people would say it probably sounds exactly the same! [laughs] But he doesn't make music anymore, he does sculpting and metal welding.

In fact, when he left the band, there was such an enormous hole, royalties-wise, from advances that our rather corrupt management had taken. I don't think there's any way he's ever going to see any royalties from XTC--except that this BBC set comes out on our label, Idea Records. So, we're not owing to Virgin for anything, and we can actually pay him some money. It will be his first royalties. It will be Terry's first royalties as well. But, at least, because now we can control the money, we can afford to pay these people.

Listener: Now I've got a delicate question to ask--and if this is something you don't want to discuss...

Partridge: No, I'll answer anything.

Listener: Hearing these live recordings, has it whetted your appetite to play in front of an audience at all? Is there any chance of...

Partridge: No, I really think I've got that out of my system. I did too much touring, it really shook me up. And when I started to get panic attracts on stage, that really finished me off. And I felt, No, this is not for me.

And I'm glad we did stop. Because I think our music got broader, and a lot better. And I think if we'd have continued touring in the way we were doing, I would have thrown in the towel and said, "No, I don't want to do this anymore."

But, it hasn't whetted my appetite to say, "Yeah, wow, I must get up there and shake myself about!" [laughs] I don't feel that these days. I mean, there's a lot of things I want to do music-wise. But, none of them are of the rock 'n' roll, shaking yourself about onstage variety.

Listener: Fair enough.

Partridge: I think that's a young man's game, to be frank. I think it's best done by young gangs with guitars.

Listener: One more question, which is actually from my friend Pat Meanor: What question or questions are there that interviewers don't ask you, that you wish they would?

Partridge: I like all the really banal ones! The ones that lead on to interesting stuff that gets pulled out--like favorite cereal, or favorite color, or you know, those kind of things. But, people always shy away form those questions, because they think that there's not going to be an interesting answer. [laughs] Sometimes the answer is very simple, but can lead on to interesting speculations.

Listener: There are, in fact, references in the book to Cocoa Pops...

Partridge: No, I've really gone off those. [laughs] In fact my choice of breakfast cereal right now is Crunchy Nut Cornflakes--I'm not too sure whether they're called that in America--and I screw up the bags, so they're sort of smashed up to sort of dust. So: Crunchy Nut Cornflake Dust. Topped with Alpen.

Listener: Alpen's wonderful, but you can't get that over here.

Partridge: Oh, it's great. It's the powdered whey that makes it so fantastic. Yeah, and then I put banana on top of that. But, the Crunchy Nut Cornflakes have to be mashed up. I crunch them all up into dust in the bag.

And soy milk--that's a revelation for me. It's great stuff. You should get the sweetened stuff, sweetened with malt or apple juice. You won't want to go back to milk.

Listener: I don't anyway, so there you go. We've visited four or five times, and every time we just fill our suitcases with Alpen.

Partridge: You don't fill them with Marmite, then?

Listener: Oh, God, no. I haven't actually tasted it. I've just smelled it.

Partridge: [Laughing] Hah! Every American that smells Marmite says it smells like sort of liquid liver.

Listener: That's as good a description as I could think of.

Partridge: But, it's great stuff if you're raised with it. It sort of smells like radioactive by-products, but if you're raised on it, it's wonderful.

Listener: There you go: As a fan, I'd rather know about that than--well, what's that Ray Davies line, "Ask about my politics and theories on religion..."?

Partridge: Yeah, I'd much rather read what color they like and things like that. I think that's more revealing.

Listener: So tell me: Is your life in music at all close to what you pictured when you started the band some 26 years ago?

Partridge: No, the goals keep changing. You know, some goals you're never going to reach and so they're still--they still sort of hang there. Or, some goals you never reach, and you think, well, my personality's changed and I wouldn't want that goal now. And new ones form. New ones are continually looming out on the mist. So I've achieved more then I ever thought I would. But, then again I've achieved nothing. I'm still very hungry to keep doing it.

Listener: And XTC will continue, Dave's departure notwithstanding? You and Colin are going to continue to make XTC records?

Partridge: We'll continue to make records. I mean, that's what I consider we've been since, really, since Terry left. And the band seemed to function as a live kind of engine. I've thought of us as being record-makers. Which Dave found very hard to grasp. But now he's gone, and I think we're even farther done the road of being record-makers. Which is fine. You know, that's what I want to do. I have a hell of a lot of records in me, different types and different things I want to get into. I just hope I can continue to be able to fund doing them.

I'm just getting started, that's the thing. What I do now is not going to be to everyone's taste. It may not be to a lot of younger people's taste. And it's certainly a sense of trying to surprise myself. Because if I can't surprise me, who the hell can?

Go back to Chalkhills Articles.

Reproduced by permission of the author.