MOJO

March 1999

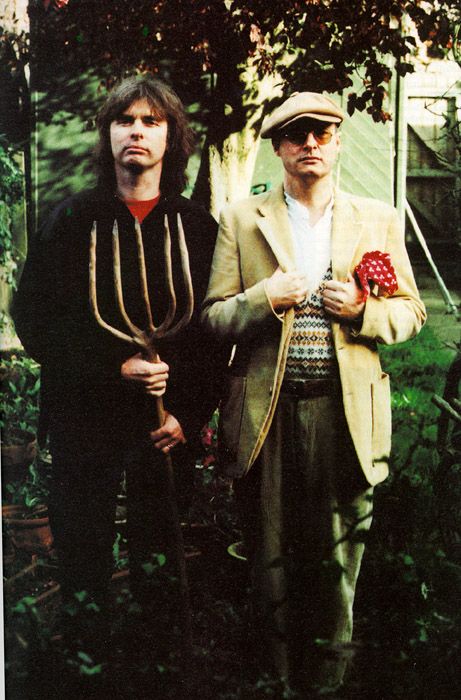

Here's one of our Colin and Andy, still together after 24 years. You might think it's been nothing but rural tranquility down on the farm. But as the couple present the first XTC album in seven years, Chris Ingham uncovers a blood-soaked saga of, shall we say, ‘musical differences’. |

XTC - 'Til Death Do Us Part

Like the set of a James Bond finale, the converted power station of Metropolis Studios is all walkways, bridges and industrial lifts. But at the far corner, in a tiny spotlit room with speakers the size of Wiltshire, something quietly momentous is happening. XTC are mastering Apple Venus (volume 1), their first studio album in seven years.

It's easy to surrender to an unmistakable feeling of wonder as this dramatic music, perhaps XTC's most sumptuous feast yet, is unveiled at intoxicating volume, in mesmerising detail. Transfixed before the commanding orchestral sounds and affecting compositions, it's been so long and the music is so good you're in danger of getting emotional.

The album is to be pressed as a collector's vinyl edition; Andy Partridge - XTC's Führer genius disguised as pasty-faced bumpkin - says that he's looking forward to seeing the swarf curling off the acetate as it is lathed, which sparks off a word-associated memory. "When I was a teenager, I always wondered what it would be like to have sex with a tub of Swarfega. I always imagined a lovely slurp. As it turned out, it's about the only thing I haven't attempted sex with. I suspect it might burn." No-one turns a hair.

Colin Moulding - bassman, second writer-in-command, handsomest man in Swindon - floats around the shadows, flicking magazines, sometimes looking up to listen, alert but composed. Is he nervous? "A little concerned about the cost." Have you been to a cut before? "I don't know. I think this might be my first." Very cool - as only the partly disconnected can be.

Andy, in contrast, spends much of the time lurking by the control desk and confesses to "getting a bit wound up. Five years struggle, a year putzing around recording the thing. I can't shit, personally. . . How's it sounding, Tim?" he asks, sniffing for affirmation. "Sounds good," replies the mastering engineer. "Sounds like a record." A comforting thought for a band who must have wondered if they'd ever make a record again. Sounds like a record. Thank God for that.

The Live Years 1975-1982

By July 1975, The Helium Kidz' brand of Wiltshire glam rock ("Blimey! It's The Swindon Dolls," teased one wag at their London club debut) had evolved into sparky, sci-fi quirk-pop. It was time for a change of name. They toyed with The Dukes Of Stratosphear, but eventually settled on XTC after Jimmy Durante's exclamation on finding the lost chord ("Dat's it, I'm in XTC!").

XTC were initially a five-piece, comprising Andy Partridge (guitar, vocals), Colin Moulding (bass), Terry Chambers (drums), Jon Perkins (keyboards) and Steve Hutchings (vocals). Hutchings was a London-based semi-professional, drafted in on the recommendation of a girlfriend of Andy's who had heard him singing while he was cleaning windows. Although he had an image problem - on-stage he would unzip his boiler suit to reveal his pubic hair, convinced it would turn on the girls - the band hoped his experience would help them secure a recording deal. It didn't.

Hutchings was eventually sacked in June 1976 and Perkins, whose Davoli synthesizer had significantly contributed to the band's developing sound, quit in November 1976 to join The Stadium Dogs. Andy Partridge answered a 'keyboard player seeks band' advert placed by Barry Andrews, a bright, balding, 20-year-old cabaret organist. Partridge and Andrews bonded over much beer and Barry was in the band without playing a note.

The first rehearsal was a shock. Andy: "He sounded like Jon Lord from Deep Purple; fuzz box, wah wah pedal, bluesy runs. I said, You don't have to play like that, you can play like us if you want. The next rehearsal, he was like a maniac, like if Miró had played electric organ. Fantastic. I think he felt at home once he'd been given permission to be himself." The cheap, 50's sci-fi sounds and maverick approach complemented Partridges ambition to combine the banal with the confrontational. The band was settled.

By this time the band had signed a management deal with Ian Reid, an ambitious ex-army officer who owned a Swindon club called The Affair, and who set about interesting the punk-hungry record companies in signing the band. XTC weren't really punk - Andy was distinctly underwhelmed by the Sex Pistols' TV performance of Anarchy In The UK - but they were young, improving by the gig, and more than spunky enough to ride into town on the energy of the post-Pistols New Wave.

Reid did a deal with the Albion agency (who managed up-and-comer like The Stranglers and 999), which opened the door of hip venues like the Hammersmith Red Cow, The Nashville Rooms and Islington's Hope And Anchor. In exchange, he put Albion's bands on at The Affair. The first six months of 1977 saw XTC impress a lot of the right people, get their first John Peel session after he saw them Upstairs at Ronnie Scott's, turn down CBS and Harvest and see the Virgin and Island representatives resort to fisticuffs in an argument over who was to sign the band.

In August 1997, Virgin signed XTC and put them into Abbey Road for a day with John Leckie to record Partridge's Science Friction and She's So Square and Moulding's Dance Band for the 3D EP. Soon after into Virgin's baronial studio The Manor to bang down their debut album, White Music. Cocky, smart sounds where "Captain Beefheart meets The Archies", as Partridge has it, in a 50s-style future, it turned a few heads and the press loved it. "It's just everything we'd ever listened to," says Andy. "The Beatles, Sun Ra, Atomic Rooster - anybody who'd done anything we liked. We just thought it was dead original. I couldn't listen to it for years, but I'm nearly through the embarrassment. It's not crap."

Placed on a weekly wage of £25 each, XTC charmed the press with their witty group-chemistry and, being perpetually on tour, became an electrifying live band. Partridge's twitchy, bug-eyed stage persona perfectly complimented his jabbing abstract-hiccup vocals and skank'n'scratch guitar, while Barry Andrews, with his running-repairs-at-the-organ, Mad Monk Of The Keys antics had developed conspicuous presence. The Moulding-Chambers rhythm section was a precision powerhouse and with tempos way up on the already brisk recorded versions, audiences were pummeled into a frenzy. Chart success eluded them however; their second single, Statue Of Liberty, was banned by the BBC for the "I sail beneath her skirt" line and This Is Pop didn't quite do the job either, despite a sparkling re-recording produced by Mutt Lange and appearances of kids' TV shows like Tiswas and Magpie.

Word got back that Brian Eno was a fan, and they asked him to produce the second XTC album. He refused, convinced they didn't need a producer. Virgin and the band disagreed and went back to Abbey Road with John Leckie. Meanwhile, Barry Andrews had written several songs and was expecting them to be rehearsed and recorded. Andy: "I honestly tried to get behind them but I was really worried we hadn't made enough impression on people to veer off track. Barry didn't have much of a singing voice, it was more a kind of an explaining voice. Musically, they were straighter and I tried to put my personality on them. But I think he resented that I was patently worried."

Bad feeling brewed and, trying to redress the balance of power, Barry would take Terry and Colin out drinking, not inviting Andy. After five of his seven submitted songs were dropped from the finished album, Barry was confessing to journalists that he thought the band would "explode pretty soon", and three months after the release of Go 2, during their first trip to the States in December 1978, Barry quit. No-one tried to stop him. Andy: "His desire to be cartoon working-class would be at odds with my striving for some sort of art life. He enjoyed undermining what little authority I had in the band. We were bickering quite a lot. But when he left I thought, Oh shit, that's the sound of the band gone, this space-cream over everything. And I did enjoy his brain power, the verbal and mental fencing."

A palpable step forward, Go 2 impressed with its experimental production and arrangements and was critically applauded, not least for the marketing satire of the sleeve ("This is a record cover. This writing is the design. . .", etc, put together by Hipgnosis) and the Go+ EP that came with the first 15,000 copies, collecting five bold and strange dub mixes. It even reached number 21 in the album chart.

Thomas Dolby was among the applicants for the vacant keyboard chair but Andy had other ideas. "It would have been tough for any keyboard player to have fitted into such ludicrously idiosyncratic shoes. Dave Gregory being invited in was like us saying, Let's start again. We knew he played his instrument very well. And we needed somebody quickly who could competently carry a musical load, touring-wise. It was a panic buy that we thought would have guarantee to it. I was relieved he didn't write."

Andy had already helped change Gregory's life when in 1972, depressed with diabetes and unrequited love and having not touched a guitar for two years, Dave walked into a Swindon record shop where the assistant was a certain 'Rocky' Partridge, so called because of an early guitar mastery of The Beatles Rocky Racoon. Rocky played him The inner Mounting Flame by The Mahavishnu Orchestra and, knocked out, Gregsy saved up and sent off for it from Richard Branson's Virgin mail-order company. The clouds slowly lifted. Dave: "One of the watershed moments in my musical education."

Involved with various local bands, Dave had watched the progress of XTC with pride and a little jealousy - he'd auditioned for them before Barry joined - and was thrilled to be offered the gig, though he was also mildly anxious about alienating Barry fans in XTC's growing audience. "I was the archetypal pub-rocker in jeans and long hair," remembers Dave. " But the fans weren't bothered. Nobody was fashionable in XTC, ever." After a few gigs during which his amplifier volume was modified, it was clear that Dave would bring a positive, musicianly refinement to proceedings." "I didn't think it would last very long but things just got better and better."

A drum sound that would "knock your head off" was one of the priorities for the third album and, after hearing Siouxsie and the Banshees' The Scream, XTC hired producer Steve Lillywhite who, along with engineer Hugh Padgham, provided the panoramic percussive impact that was required, virtually making everyone's names in the process. Terry, now the sonic focal point, came into his own with crisp, imaginative patterns including the upside-down backbone - a misinterpretation of a Partridge instruction - to XTC's breakthrough hit, Making Plans For Nigel.

A thundering, infectious pop tune about an introspective child with overbearing parents that sunk much further into the national consciousness than its modest chart placing (number 17) would suggest, Nigel was a Colin Moulding song, as was the previous near-hit, Life Begins At the Hop. Colin: "I wanted to ditch that quirky nonsense and do more straight-ahead pop."

With its obvious hit potential, much recording time was spent on Nigel, much to Andy's annoyance. "We spent a week doing Nigel and three weeks doing the rest of the album. Nigel did us nothing but good but Colin became gently unbearable. He'd already had a smidgen of attention with Hop, which had puffed up the old gills a bit. Then with Nigel he got a superior 'just carry me there and feed me chocolate cake' manner". . . Colin is astounded at the suggestion: "Blimey! Steady on old chap. I have a natural propensity not to be cock o' the walk. It's not in my demeanor. I think that Andy was actually a straw's width away from chucking in the towel. He was well pissed off."

The impressively complex clatter-pop that was Drums And Wires was released in August 1979 and was, in Colin's view, where XTC's "career really started". Andy concurs: "We started becoming half-decent around Drums And Wires." Thanks to Nigel and an extended tour, there was a corresponding upturn in career profile. Unfortunately for Colin, those heady days were rather lost on him. He had left his wife for an Australian reporter he'd met on tour that summer and was only gradually realising, in the whirlwind of his career, that he'd made a big mistake. He was back with his young family by Boxing Day, 1979.

The crucial follow-up to Nigel was bungled. Virgin and the band couldn't agree on the track, but Andy was already excited by an obscure, heavy-reggae singalong of his, Wait Till Your Boat Goes Down. Released six months after Nigel, despite a production by Phil 'Bay City Rollers' Wainman (who, apparently, only managed to make it weirder), it bombed, being XTC's lowest-selling single thus far.

After the fuss made over Colin's songs and with the Moulding-penned Ten Feet Tall released as XTC's first US single, Andy was keen to reassert himself. Andy: "I thought I should be leading the band. Someone had to take charge and I thought I was a very benevolent dictator." Dave begs to differ: "We were all pretty tired and my nose was being pushed out of joint with Andy calling all the shots because he wrote the songs. He could be a little bit of a bully."

The resulting album, Black Sea, made with the Lillywhite/Padgham team, had the critics falling over themselves, and Moulding's Generals And Majors and Partridge's Sgt Rock (Is Going To Help Me) saw the band back in the UK charts, the latter's "keep her stood in line" sentiment provoking feminist hate-mail. Andy: "I wrote it as a bit of fun, rehearsed it and started to think, Why did I write this? Then the record company go, 'Brilliant, it's a single.' I wish I hadn't written it, this is crass but not enjoyably crass. We did it on bloody Swap Shop with Know-all Edmonds."

Having given his old acoustic guitar away on that very kids' show, Andy composed much of the next album on a new Yamaha acoustic. Dave not only bought a Rickenbacker 12-string but awoke his dormant keyboard skills, feeling happier about the band's musical role. Relaxing their self-imposed rule not to record arrangements that couldn't be reproduced live, English Settlement - a double produced by the band and Hugh Padgham, and issued in February 1982 - was their most ambitious and accomplished set to date. Partridge's Senses Working Overtime was the single and, with it's odd, medieval-sounding verse and chiming, countdown chorus, became XTC's biggest UK hit.

Meanwhile, Ian Reid kept XTC touring constantly in 1980/81 with a second trip to Australia and hop into New Zealand (where they were surprised to find they were stars), and visits to the States where they were building a cult following. Robert Stigwood told them they were the most exciting band he'd seen since The Who; in Athens, Georgia they were supported by a local group called R.E.M., who included XTC songs in their set. They supported The Police in sports stadiums, while in Venezuela the police intimidated the audience into leaving one night, with the audience lighting bonfires and jumping into them for fun the next.

Mid-tour, however, Andy Partridge would sometimes literally forget who he was. Or would collapse in a fit of uncontrollable sobbing in the back of the tour van. He asked to stop touring after Black Sea but the band, record company and management wouldn't hear of it. Everyone put things down to tiredness, probably linked to the fact that Marianne, his then wife, had recently ended his 10-year Valium addiction by flushing the tablets down the toilet. As the English Settlement promotional duties approached, Andy got more and more tense; then, in February 1982, just before the band performed Yacht Dance and No Thugs In Our House on BBC's Old Grey Whistle Test, he froze. "I was petrified. It was fear of not being allowed off the treadmill, of being out of control and trapped." He'd already found himself virtually auto-piloting live shows. "I'd get three numbers in and I'd think, How did I get here? Where's all the money? We never saw a cent from five years of touring. It was a big worry."

Soldiering on despite dry retching, nausea and agonising stomach pains, Andy's nightmare climaxed when he ran off the stage one minute into an important live-broadcast gig in Paris and, in the teeth of the French promoters' fury, flew home to find out what was wrong. Hypnotherapy revealed that Andy had developed a chronic psychological aversion to live performance and the touring life. "My body and brain said, You're hating this experience I'm going to make it bad for you. When you go on stage I'm going to give you panic attacks and stomach cramps. You're not enjoying this and you haven't got the heart to tell anyone you can't carry on so I'm gonna mess you up."

European dates were cancelled but Andy was coerced into attempting a US tour. He made it through one gig but, after the soundcheck for a sold-out show at the Hollywood Palladium on April 4th, 1982, "I couldn't get off the bed. My legs wouldn't function. Walked to Ben Frank's coffee shop, where we'd all agreed to meet, in slow motion like I had both legs in plaster, trying not to throw up. I got in there, they knew what I was going to say." Acquiring a hospital certificate to avoid having his "legs genuinely broken" by the promoter, the band skipped town. The live career of XTC was over.

The Studio Years: 1982-1992

Most people connected with XTC thought that, if they gave Andy enough time, he'd get over it and want to play again. A fragile Partridge embarked on more hypnotherapy, frightened he had become a Syd Barrett-style rock casualty. He locked himself away in his newly-acquired Edwardian semi in Swindon Old Town, terrified of leaving the house to do the shopping, let alone to meet the new neighbours as Marianne suggested. "It got to the point where if I touched the front door knob, I wanted to throw up."

Andy continued worrying about where all the money the band had generated had gone, and was losing faith in Ian Reid, who had refused to help cover the debts incurred over the tour cancellation, claiming XTC owed him money. In an attempt to sideline Reid, the band renegotiated the record contract guaranteeing Virgin six more albums in return for an advance to settle immediate cancelled tour debts. They also ensured all future royalties and advances were directed into their own deposit account and started paying themselves their first-ever half-decent wage.

Andy had spent the summer of 1982 recuperating, gingerly strumming his acoustic in the back garden and writing songs, and by September was ready to rehearse the next album. Terry, openly appalled at Andy's 'cissy' behaviour had to be persuaded to return from Australia, where he had become a father, and reluctantly installed his new family on a Swindon housing estate. Steve Nye, who had impressed Andy with his work on Japan's Tin Drum, was enrolled as producer and rehearsals began, but it was clear Terry's mind was elsewhere. "On Love On A Farmboy's Wages I wanted tiny, cyclical, nattering clay pots - he didn't like that - 'a bit fucking nancified'. One day I gave him a cup of Earl Grey tea. He spat it out said, 'Fuck me Partridge, you trying to get me to drink a cup of fucking scent?' That's Terry."

Uninterested in Andy's ornate percussion requirements, unimpressed with the new songs and feeling bad about stranding his Australian wife in rainy, grey Swindon, Terry quit. Andy: "An enormous shock, but an exciting shock." Ex-Glitter Band drummer Pete Phipps was recruited at short notice for the sessions that would produce the album Mummer and immediately brought the subtle, pastoral Partridge compositions to life.

Meanwhile, Virgin had attempted to keep the XTC career buoyant by releasing a best of compilation, Waxworks, with the B-sides freebee Beeswax enclosed with the first 50,000 copies. It bombed. When the band presented and oddball, single-free new album, XTC's then A&R man Jeremy Lascelles rejected it. Andy: "He asked me to write something a bit more like The Police, with more international flavour, more basic appeal. At a time when I was crawling my way back up after making myself Mr Cunt Number 1, I felt rather destroyed."

XTC's A&R man at Virgin Jeremy Lascelles denies The Police suggestion: "I think I mentioned Talking Heads. When you're talking to artists about making records, you're throwing ideas around, ridiculous suggestions can spark people off in a direction. Andy likes to portray us as the strict, stern schoolmasters, but we never wanted him to compromise at anything we thought he was good at. Here were very talented songwriters - surely, surely, surely they can come up with that elusive thing that is a hit single. That was our psyche."

Andy came up with the boisterous but not overly commercial Great Fire, which was accepted as a single but flopped. Virgin suspended Mummer's release and demanded more songs. XTC refused but agreed to some remixes, including Colin's Wonderland, which was released as a single and also flopped. More songs, said Virgin; no, said XTC, already way over budget. Mummer finally crept out in August 1983, but with no band or company action behind it it sold appallingly - despite the agrarian gem that was the next single, Love On A Farmboy's Wages. In 18 months, XTC had gone from Top 10 hits and critical superlatives to being ignorable, arcane eccentrics. "Your average English person probably thinks we split up in 1982," suggests Partridge. He's probably right.

For their next record, Andy was convinced XTC had found their George Martin in David Lord, owner/engineer of Crescent Studios in Bath and former Director of Music at Bath University, who impressed the boys with the fact that he had once turned down Paul McCartney's invitation to arrange She's Leaving Home. After trying out Lord with a festive single, Thanks For Christmas - released under the pseudonym The Three Wise Men but sounding rather like limp XTC with sales to match - the band struck a deal with him to work as long as they needed on the album and embarked on months of experimental tinkering.

Hours of programming the ubiquitous mid-80's percussion tool, the Linn Drum, sapped Colin and Dave's enthusiasm and it was years before Dave could bear to listen to the elaborately noisy result, The Big Express. Virgin threw £33,000 at a promotional video for the single All You Pretty Girls but to little avail; released in October 1984, The Big Express joined Mummer in the box of XTC records that no-one wanted. Andy won't admit to being fazed. "Call me stupid, but these were good records. If you bastards don't want to buy 'em, what can I do? I had faith in my art."

Andy had been doing some production work, including a Thomas Dolby single and Peter Blegvad's album The Naked Shakespeare. In November 1984, he went to Monmouth with John Leckie to produce recent Virgin signing Mary Margaret O'Hara. Despite getting on initially, devout Catholic O'Hara discovered Partridge was a lapsed Anglican and Leckie a follower of a controversial Indian Guru who advocated free love. Partridge and Leckie found themselves fired because the "vibes weren't right".

To fill the unforeseen window in his schedule John Leckie agreed to tackle a pet psychedelic project of Andy's inspired by Nick Nicely's ingenious pastiche single, Hilly Fields 1892. Promising to return a record for £5,000, john and Andy persuaded a reluctant Virgin to fund The Dukes Of Stratosphear. Using only vintage equipment and recording in no more than two takes, the band packed the tracks with period detail. Entering into the spirit, everyone adopted psychedelic alter-egos - Sir John Johns (Andy), The Red Curtain (Colin), Lord Cornelius Plum (Dave), E.I.E.I. Owen (Dave's drummer brother Eewee), Swami Anand Nagra (John Leckie) - burnt incense, wore paisley and generally had more fun than they had done for some time. Andy: "I had to get it out of my system and did in grand fashion. Dave Gregory took to the Dukes a bit too much. Elephant jumbo cord flares, big white belt, beads - we were a bit worried." The six-track mini-album 25 O'Clock was released on April Fool's Day, 1985, thinly disguised as a recently discovered '60s relic, and to everyone's amazement, even embarrassment, outsold The Big Express. Andy: "The amount of bands that have contacted John Leckie because of that record is amazing. Kula Shaker, the Shamen, The Stone Roses, they all wanted him to produce them because of the Dukes."

Although English Settlement had made a healthy profit, the band also received a huge unpaid VAT bill for the time Ian Reid was in charge of their finances. On legal advice, XTC sued Reid who immediately counter-sued for unpaid commission on royalties. As litigation ensued, Virgin were legally required to freeze royalty and advance payments and divert publishing income into a frozen deposit account. Eventually, with the case dragging on for years, XTC were forced to live on short term loans from Virgin and PRS payments for airplay. Early in 1986, the band met with Virgin for what was expected to be a routine album planning but, according to Andy, "was more of a veiled threat that if we didn't listen to their advice and sell more than 70,000 copies, we could find ourselves without a label. I was being leant on by Colin and Dave so I felt obliged to bite my tongue."

Geffen, XTC's US label, were pushing for and American producer for the next album and Todd Rundgren's name came up. Dave was genuinely thrilled by the potential of the Rundgren-Partridge meld: "Of course, I'd reckoned without the ego problem." Within days of receiving the demos, Todd had selected and programmed the running order into a concept based on the passing of a single day. He'd even devised a cover and title; Day Passes. Distressed to see what he considered his strongest songs "fall outside the circle", Andy's alarm bells were tinkling. "It was scary but actually thrillingly professional too. But he picked everything of Colin's and half of mine. And I thought, Am I that crap suddenly? Is Colin that brilliant?"

In his Utopia Studios complex in the Catskill Mountains in upstate New York, Todd was boss - "ludicrously bright chap, shockingly apt arranger," maintains Andy, but from the band's point of view also arrogant, sarcastic and coldly impervious for Andy's usual tactics for getting his own way. Dave: "It was just nasty and unnecessarily unpleasant. Todd got the measure of Andy's conceit, shall we say, and played on it. He'd deliberately belittle him if he thought he was getting too big for his boots. Andy rose to the bait every time."

Staying together in the less-than-salubrious guest living quarters and getting rather scratchy with each other, Colin took one bass part instruction too many from Andy and "did a Ringo. Andy was not enjoying being dictated to and I think he was taking it out on me a little. I was a little hyped and we were all a little homesick. I left and came back and it was never mentioned again." Todd persuaded him to at least finish his work on the album and Colin agreed but banned Andy from his sessions. After a particularly brutal band row, XTC flew home, leaving a detailed list of instructions for Todd.

Back in England, the mixes arrived. The band hated them, and insisted Todd did them again. Todd phoned Dave in the middle of the night to tell him exactly what he thought of that but did them anyway. After some third mixes, Todd signed off and XTC had their album, Skylarking. "At the time I felt like disowning it," admits Andy. "I thought, Jesus, this man's killed our career. But in reality, he did us a great favour. If he wasn't so personally poisonous, I would have loved to work with him again."

Rejecting Andy's initial cover idea of a close-up of male and female pubic hair intertwining with flowers (deemed undisplayable by retailers), Virgin were nonetheless enthusiastic about the album and pressed ahead with the Moulding-penned Grass as the first single. Its B-side, rejected from Skylarking, was an odd, angry little atheist song of Andy's called Dear God, which Virgin disliked for the "whiny American kid" singing the first verse. Andy himself describes it as "a petulant failure", but American

college radio had started playing the import single and Geffen, bombarded with enquiries about a song of which they knew nothing, recalled the album and re-pressed it with Dear God reinstated.

Andy: "Mail started to arrive and it was half 'you've voiced what I've been thinking for years' and half 'you're going to roast in Hell'." A Florida radio station even received a bomb-threat and a disaffected student held up a high-school secretary at knife-point in New York State, demanding that Dear God be played over the school public address system. Dear God helped Skylarking sell a quarter of a million copies, and XTC entered 1987 having found a whole new audience of American college kids.

The Dukes Of Stratosphear were reactivated, this time at Virgin's request, though Andy wasn't keen. A £10,000 budget saw them return 10 John Leckie-produced tracks for the Psonic Psunspot album, but with parts of Skylarking being distinctly trippy and parts of Psunspot barely pastiche, the distinction between the psychedelic japes of the Dukes and XTC's real output was getting finer.

Meeting Paul Fox, a keen young American who was mooted as the producer of the follow-up to Skylarking, Andy sensed he would get more of his own way this time and, accompanied by the Partridge and Moulding families, XTC headed to Los Angeles. Between May and September 1988, an optimistic band recorded the technicolour extravaganza that was Oranges And Lemons. With recording complete, however, Andy started to dwell on all the money that was being lost and the pointlessness of future income given the ongoing cost of the litigation. Depressed and drinking, he even relinquished supervising the mix in order to get home and pull himself together.

Around this time XTC signed a one-album-at-a-time management deal with one Tarquin Gotch, sometime manger of The Lilac Time and Dream Academy. Regarding the five-year-long lawsuit against Ian Reid, "he finally opened our eyes to the fact that we'd been pissing away a fortune." Andy recalls. "Tarquin took us to another lawyer for a second opinion, who had the case grasped and sewn up in a matter of hours." XTC finally settled out of court with their former manager in 1989, five years after the lawsuit had started.

Oranges And Lemons hit Number 1 on the American radio college charts and was on the way to selling half-a-million copies; success on which a tour could lucratively capitalise. Any was still unprepared to face a live audience but suggested an acoustic-guitar tour of US radio stations. (Unimpressed by the sound MTV achieved, Andy had suggested a stripped-down acoustic set to them, "so they couldn't screw the sound up", unwittingly starting the 'unplugged' trend.) By the end of the radio tour, having got the half-hour set off pat, Andy admitted to enjoying himself, even getting through a show with an audience of 250 people without too much trouble. "I liked the anti-showbusiness of it. You weren't expected to be fabulous."

Gotch had one last attempt to get Andy on some proper, money-spinning live shows. He fabricated the idea, with Dave and Colin's connivance, that they would tour as XTC with Thomas Dolby taking Partridge's place. Andy: "I had actually suggested they tour without me; if Brian Wilson could do it, why couldn't I? But when he said, 'Look, we'll get someone in who looks a bit like you and who's got a bit of a name, Tom Dolby', that put my nose out of joint. I said, well perhaps I could come on for a couple of numbers towards the end, and he said, 'Come on for the whole fucking set, you idiot.' Smelt of ruse." With Andy refusing to budge, Tarquin Gotch wished XTC well and retired gracefully.

Things had got so tight for Dave - being the non-writer of the band, he received only the 10 per cent share of PRS royalties due his contribution to the band - he'd had to work as a rental car collector at the back end of 1987. Now in 1989, he was part of a 500,000-selling album and unable to make any touring money on the back of it. Dave: "There was no point in insisting Andy went on tour. What's the point of pushing him to a nervous breakdown? He's never been motivated by money; he's a true artist in that he's inspired by his gift. In fact, if he gets the inkling that you're trying to make money out of him, he will absolutely refuse to do anything at all."

Preparation for the next album started badly. Of the 20 demos submitted to Virgin, Jeremy Lascelles liked only one or two and wanted more. Lascelles: "I said, Andy, you've written this song before, it's another Beach Boys song, another Beatles song. . . He wasn't really stretching himself - it was good but a bit comfortable. He didn't like me saying that and I didn't play them to anyone else, which he took to be a great slight." Lascelles didn't like the second batch either and Andy, considering the songs some of the best he'd ever written, asked to have him taken off the job. "He was a bit of a bane. He once said if I could write songs like ZZ Top, that would be a good way for us to go! I just thought for a band of our standing we should have been nurtured." Lascelles: "I think we were incredibly supportive. The showdowns were very minor. We gave Andy and the band free rein to do what they wanted. I don't think they were interfered with. We commented, suggested, offered advice about how they might do what they want a little better or more commercially; that's what our job was."

Producers were proving a problem, too. The Padgham/Lillywhite team were going to reunite for half their fee but didn't turn up and so were sacked, John Paul Jones was too expensive and, according to Andy, "Steve Lipsom said, 'I love the music but what the fucking hell are you singing about? You want to be writing lyrics that a 16-year-old girl putting on her make-up can sing.'"

Eventually they ended up with Bonzos/Elton John legend Gus Dudgeon. "He pulled up in one of his personalised numberplate flashy cars, satin tour jacket, spray-on white satin trousers, medallions, two-storey hair; I thought, This is so wrong," recalls Andy. "He'd read about me and Todd so immediately adopted this Mr Amiable stance. Gus is old school, full of blusters and bluff - 'Elton gave me this Rolls-Royce and I said, Oh Elton darling. . .' We called him Guff Dungeon because he was so farty, literally flatulent. 'Are you going in the Guff Dungeon yet?' 'Let's give it half an hour, eh?'" For his part, Dudgeon recalled, "You can flip between thinking Andy's superb and wanting to fucking kill him, in a matter of minutes. Half the time he doesn't realise the effect he's having on people."

It puzzled Dudgeon why such and insular artist bothers hiring a producer at all, if all he is going to do is interfere. Dave: "Andy is a great artist and a great writer but he is not a producer. A producer has to know how to get what the artist has to offer into the minds of people who just want some great music, as opposed to an artist just throwing his weight around and showing how clever he is." Andy: "Apart from Todd, we have gravitated toward engineer producers, people who don't mess with you musically, so you end up producing yourselves. Dave and Colin did resent that because it meant I ended up telling them what to do. I'd have to do it through the producer, this conduit, because they wouldn't take it from me. I was doing my darndest to produce the album but it was diplomacy hell."

Gus made it clear that he did not want Andy at the mix for the album that had become known as Nonsuch. Andy turned up anyway and the resulting row and first three mixes ("These mixes give off icy blasts," said someone at Virgin) left Andy no choice but to sack Gus and hire Nick Davies, whose work on Genesis' We Can't Dance had recently impressed him. Nonsuch was finished with Andy at Nick Davies' elbow.

While rehearsing for a European acoustic radio tour Andy again found himself crippled with anxiety. With no hit singles (although The Crash Test Dummies eventually had a Canadian Number 1 with The Ballad Of Peter Pumpkinhead - "Our version was rather swingier than theirs, actually," bitches Andy) and no ingenious promotional activities, Nonsuch fared slightly worse that the previous two albums, but well enough for Virgin to expect a follow-up. The next batch of XTC demos had already arrived and it looked like business as usual.

The Strike and Rebirth Years: 1993-1999

Andy and Colin tell the tale with humour, but you can feel the hurt. Andy: "So we made Nonsuch and there was just blankness from Virgin: ‘What are we going to do about this? No-one's going to buy this.’ They just let the thing come out and die. The real slap in the face was when they put out about 5,000 copies of Wrapped In Grey as the third single. I thought, Wow, something a bit chewier, a bit of quality there. And they withdrew it from sale. I thought, that's it, they've suffocated one of our kids in the cot, they've murdered the album, basically through ignorance."

Paul Kinder, XTC's A&R man in 1992, puts things into context: "Virgin had just been sold to EMI and was in turmoil. People were being fired daily, all sorts of harsh decisions were being made. This obviously had an effect on XTC and numerous other artists at that time. I don't think they did a bad job deliberately, it was just circumstances. Virgin always had a strong feeling for XTC."

Virgin wanted nothing to do with Andy's latest wheeze -- an album of spoof bubblegum pop. "Nicely banal, pitched around 1970, a dozen tracks about sex -- Lolly Let's Suck It And See, Bubbleland, My Red Aeroplane -- all in bubblegum form. I played them the demos and it was like the scene from The Producers where they hear Springtime for Hitler. Open jaws. I was virtually offering them this thing for free and they couldn't grasp it. It was just one more drop in the Virgin pisspot which was really overflowing by now."

When XTC had settled with Ian Reid out of court, they had been forced to adjust royalty rates in Virgin's favour to cover resulting debts which, along with the fact that that the original 1977 low-royalty negotiation remained the basis of their deal, left them in the frustrating position of never being able to go into profit, despite healthy sales. Paul Kinder admits now the position suited Virgin but agrees the band were in a predicament. "This is the ideal situation that any record company wants -- they do not want their artist to recoup. Having said that, XTC did have appalling management for a number of years. Usually if a manager has got any kind of business acumen he will renegotiate the contract to get a better royalty. A record company expects this, which is why they keep royalties low initially. It's just business really. Nobody addressed the contract for XTC."

Andy: "I just said, Look, our deal is so badly stacked against us we're never gonna make any money. You've made a ton of money: can you make our deal better or let us go so we can sign a sensible deal with a label that doesn't murder our singles. And they said no. We were earning them enough money in ticking-over terms but they wouldn't better our deal and wouldn't let us go. So I just said right, the only thing we can do is not record you any music." Paul Kinder: "What XTC wanted and what Virgin were prepared to do were poles apart. The contract was so old it got to the point where Andy wanted the moon and Virgin weren't prepared to give it him."

Dave (who thinks the strike may even have been his idea initially) and Colin were entirely behind Andy's resolve and the band lay fallow for years, unwilling to record as XTC because Virgin would have owned the results. Colin played the odd session, Dave played sessions for Aimee Mann, among others, Andy co-wrote with Terry Hall and Cathy Dennis and released an exquisite minimalist ambient album with Harold Budd, Through The Hill. He watched with amusement as some of the next generation of Britpoppers cited XTC as an influence. What a time to be on strike. "It was perfectly apt. It fits with the inherent crapness of the story."

He even tried producing Blur. "It was for Our Second Album Is Rubbish [sic]. The songs weren't very good and I did it for the wrong reasons, the flattery and the money. I liked them immensely, though; I saw Go 2-period us in them. I felt quite fatherly and I thought I did sterling work. They got Dave ‘Twat’ Balfe really stoned to listen to some mixes and he was rolling around going, ‘This is fantastic, you're George Martin and they're The Beatles.’ Next day he'd say, ‘Quite frankly, Andy, this is shit.’" The Blur/Partridge collaboration was not to be.

Personal lives got complicated in this period; Colin's wife had a long illness which required him at home and Andy got prostate trouble and a scary ear infection that left him temporarily deaf. And his wife let him. Andy: "I got divorced which was horrendous. I went through a lot of ill-health stuff which is slowly sorting itself out. Also I was drinking rather too much. It was all linked in with the frustration of the situation. The one thing I think I'm good at -- making records -- I wasn't allowed to do. I was ultra-depressed but I saw that the extreme depression was something that could be cured. Now I was out of that marriage, if I stop drinking, if we could get back to making music, I could be happier. I'm an optimist -- no matter how black it gets, it can be cured."

The stand-off with the record company didn't stop them attending the 25 Years Of Virgin party. After all they'd been sent a drinks token. Andy: "By this time we were the longest-serving act -- I hate that word, it's like a poodle going through hoops or like you don't mean it, you're only acting. They invited us to this mega-party at The Manor, sent the pass and one drink token. We parked our car in a field a mile away, had a bit of trouble getting in, and they wouldn't even let us in the drink tent. I said, We've been on the label for 20 years and it's, ‘No you don't, fuck off.’ But I've got a drinks token! ‘That's a copy that, fuck off.’ Haha! It just summed up what they thought of us."

Ironically, by 1995, having refused any advances for future recordings that they weren't going to make, XTC not only went into the black for the first time in their career but also found themselves free of Virgin. Andy: "I like to think they got embarrassed and realised that what they were doing to us was not morally commendable. I like to think they met in the dark and thought, ‘These blokes are not making a living. We've had 'em all these years and we've got their catalogue and the copyright to their songs for evermore and we've stitched 'em up real good with a rotten deal so, erm, maybe we should let them go.’ I like to think that it was a guilt thing."

Desperate to get on with recording the scores of songs that had built up, XTC set about getting themselves a record deal. Andy: "I really thought the music we've been writing is some of the best stuff, if not the best stuff, ever. It's even more intensely passionate than before. As a kid, you just thought, Wow, I'd love to be in a band and make a record with my mates. And that's about as deep as it gets. So when you're in your forties and you've been through all this, it gets to biblical proportions."

With a backlog of songs that required a double album and a band resolved not to tour, most companies found it easy to pass. After being courted by Alan McGee ("a super-wank fan", according to Andy), XTC declined Creation's "pathetic start-up band deal", settling for hip little indies Cooking Vinyl in the UK and TVT in the States.

Hiring Haydn Bendall, who had extensive experience in recording orchestras, the band settled down around a keyboard and a computer to arrange the songs by committee. A frustrating episode involving Chris Difford's studio put the project two months behind. The band adjourned to Chipping Norton to record rhythm tracks with drummer Prairie Prince.

Although Dave was enthusiastic about the quality of the songs, his annoyance at the Difford episode and his perceived diabetes-aggravated mood swings meant that Colin and especially Andy came to regard him as an increasingly negative presence. Andy: "One minute he'd be quite jolly, the next minute he's ‘this is all shit, destroy it, wipe it, it's all terrible’. It got to the point at Chipping Norton where I was so depressed, I really blew up. I had a go at everyone but a lot of it was directed at Dave, telling him to pull his weight and get into it more. I don't think he ever forgave me."

Dave: "He had the nerve to sit in that control room and tell everyone, ‘You bastards are sabotaging my career.’ It was couched in such offensive terms. He was being a cunt, frankly. Haydn nearly went home. Prairie felt really terrible, he'd been working really hard and had his nose rubbed in the dirt. After that, we weren't allowed to play; nothing was up to standard. It was getting like a neurosis with him and I was losing my temper."

As it became clear that they could only afford to record one album's worth of songs, Andy insisted on leading with an album reflecting the direction he had wanted to explore back in '93 -- non-standard, orchestral texture pieces as threatened by Nonsuch esoterica like Rook and Omnibus -- with a second guitar-based album of "songs that were easier, rather idiotic in places", to be released some months later. Dave Gregory was not happy with this and uncomfortable with the current reliance on editing technology. Although he had provided beautiful string arrangements for XTC in the past, his efforts this time did not meet Andy's requirements. He considered the proposed Abbey Road orchestra as an indulgence and, when an arranger was hired, increasingly distanced himself from the project.

Andy: "You'd be doing an interview and you'd say the band's doing so-and-so, and he'd interrupt and say, ‘Band? It's not a bloody band, it's two people making solo albums and a guitarist. . . Anyway, carry on.’ Haha! Totally pulling the rug from under you. I said, ‘Look, Dave, there's nothing you can do for the next week or so, take a break, let me do some vocals.’ Within 20 seconds he'd packed away and just drove off. And the next day he dropped a letter round at Colin's house saying, ‘I resign’. I hate to say it but I wanted to sack him but couldn't bring myself to do it."

Dave recalls his departure a little differently: "I said, Look, I don't think this is the album we should be making after six years. It's the vegetarian alternative and I've been on a diet for six years and I want curry.' And I didn't want to sign to TVT records, full stop. With the way he'd behaved in Chipping Norton, the fact that he had absolutely no regard for anybody else's point of view, I said, I'm disgusted with your attitude, I can't change you, you're not going to change, so I have to go."

It turned out to be relief all round. Andy: The dynamic between Colin and I has been a lot better, fresher. There's nobody going, ‘What the bloody hell do you want to do that for?’ It's a good divorce." Colin agrees. "Being in the band was making him unhappy, as well as us, so it's better all round."

Dave, comfortable with being out of XTC and looking forward to being an appreciated sideman somewhere soon, is unable to hide his admiration of Andy's gift: "It was a bit intimidating. As an artist he was so much better than I was. I might have had the edge on him as a guitar player in those early days, but not anymore. He had a wonderful spark of originality that nobody else had. He still has that. There's nobody writing the way he does. Nobody at all.

The two remaining members can now admit that they are songwriters operating under the brand name XTC. And with a record company that promises minimal interference, XTC are looking forward to a productive period. To Dave's accusation that, two fine Moulding contributions notwithstanding, the new album Apple Venus is an Andy Partridge solo album, Partridge has a not entirely unsurprising confession to make. "Most of them have been. But I'm still interested in the identity, the umbrella of the group. When Dave suggested I make Apple Venus as a solo album, then get on and make an XTC album, I was really offended. I want to write songs for XTC, even if XTC ends up as just me."

It's unlikely XTC will ever end up as a purely solo Partridge. Although much less prolific -- for Apple Venus Moulding submitted about six songs Partridge's 40-odd -- Colin knows his characterful, modestly wry offerings are an inextricable aspect of XTC's identity. He takes some pride in having influenced Partridge's writing in the past by being the more obviously commercial writer, but long ago accepted Andy's domination of the band. "I don't want to rule the roost. As long as I get some space to air what I've got to offer, I'm happy. It's a lot of pressure to be in Andy's position rather than mine. I wouldn't give you tuppence for it."

Plans for Apple Venus are lower-key than ever. No singles, no touring, no promotional gimmicks. Andy's idea -- giving entire unknowns a free hand to make promo films with the proviso that they mustn't look like a pop video "or we're burning it" -- received a lukewarm response from the US record company. But Partridge, after having had video idea after video idea rejected by Virgin only to see similar techniques used to acclaim by other artists -- black-and-white, animation, underwater effects -- is used to such resistance and, struggling to get out of "crap yokel mode and put my professional head on", confesses these days to being virtually promo-allergic. "I'm proud of Apple Venus but I don't want anything to do with it.

It's done. I don't like wallowing. I'm not defeatist but as long as this record keeps my head above water it'll have done its job. I don't care whether people buy my stuff or not. As long as I don't drown."

Andy's notorious standards for himself and XTC means he scorns what he considers sub-standard music-making -- down on recent McCartney, Costello and R.E.M. but up on Albarn, Space and David Yazbek. "The Gallaghers? Not even on the planet, embarrassingly empty lyrics. I like music to surprise me. If

music doesn't surprise me, how the fuck is it going to surprise anyone else?" Perhaps people don't want music to surprise them. "Oh well, most people are dead from the neck up." Such standards mean he hesitates to look back at what he has achieved: "I'm never totally happy with anything we've done. But that's what keeps you going: continual, lovely dissatisfaction."

Andy manages to keep bitterness from his tone about all his disappointments save one: that this most English of bands is so undervalued in their own country. "I don't see how we're ever going to be accepted in England in a way that doesn't smack of comeback or desperation. And comeback to what? Comeback to the ignorance that we've had from you bastards for 20 years? Come back home. Sure. What a home."

Otherwise, asserts Andy, XTC have done a "pretty good job in staying optimistic. I don't feel bad because those things have shaped us. And I like the shape that we're in now. It's like the anvil thanking the hammer for all those blows. It's hardened it and it's made it better-equipped to deal with things. It's been a very expensive but well well-worth-it education. I don't resent being ripped off -- I had Rip Me Off written all over me. I get a bit sick of these Poor Old XTC stories. We've been together since '72 and we've got better -- apart from the money we're actually Rich Old XTC."

Acknowledgements: XTC Chalkhills and Children: The Definitive Biography by Chris Twomey (1992 Omnibus); XTC Song Stories By XTC and Neville Farmer (1998 Helter Skelter). Thanks to Neville Farmer and Robert Sandall.

Go back to Chalkhills Articles.

[Thanks to Adrian Ogden -- "Sic Biscuitus Disintegrat" -- and Dan Wiencek]