Musician

Issue #30, February 1981

By Roy Trakin

Both XTC and Gary Numan express a sense of the new English isolation.

Americans seem to like the car-crazy Numan,

while the pure British pop of XTC is as yet unappreciated.[NOTE: the following article has been edited for content. Originally it was an article that was written approximately 50/50 about XTC and Gary Numan, hence the references to Gary Numan. Most of the Gary Numan material has been edited out. - David Oh]

From Sergeant Pepper and Rubber Soul through Ziggy Stardust and For Your Pleasure right up to The Wall, England has always been a leader in that much-maligned genre of popular music known as progressive or art-rock. By adding either vocal phrasing, a synthesizer riff or a stray sitar run to the standard 4/4 guitar-bass-drums rock 'n' roll, the British have consistently managed to sell our own music back to us with a distinctive, stylistic flair. And, despite the inroads made by good ole uncomplicated rock 'n' roll lately, the studio continues to be an important breeding ground for experimentation and new sounds from the U.K.

As punk rock begins to fade, it has become apparent that there is a brand new generation of English art-rock bands ready to take the place of doddering dinosaurs like Yes, Genesis, Jethro Tull and ELP. Of course, these stalwarts can still fill Madison Square Garden and sell a great many records, as they always have, but their days of adventurous risk-taking and musical innovation are long gone - replaced by the smug satisfaction of commercial success. For true innovation, the discerning art-rock patron has been forced to turn to a new wave of British groups, most of whom have not quite broken through. These include more radical bands like Manchester's Joy Division, Cabaret Voltaire, Swell Maps, A Certain Ratio and Scritti Politti, who probably can't expect commercial success, as well as more accessible groups like Magazine, XTC, Ultravox and Human League, who probably can.

So, despite the proven sales potential of progressive rock, the American rock fan remains a conservative buyer slow to abandon an established entity for the novel. Which is why overly Anglophilic groups like XTC and the Jam have, so far, not caused a stir on this side of the Atlantic.

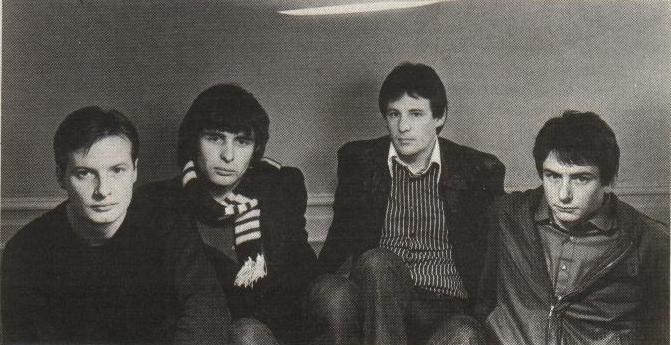

Andy Partridge and Colin Moulding of XTC are still waiting to enter the hallowed halls of Stateside commercial success. Like Numan, XTC has released four albums; unlike him, only two of the LPs - last year's Drums and Wires and the new Black Sea - have come out over here. With Atlantic recently dropping the Virgin Records catalogue, Black Sea has been picked up for distribution by RSO, for whom the band contributed a song on the Times Square soundtrack, "Take This Town". After many disappointments, leader Andy Partridge hopes XTC's breakthrough is at hand.

"I don't know what to think about America", says the exasperated Partridge. "We can only play here and hope. We're not an American sounding group. We don't conform to any popular American fantasies - we don't have any strains in our music that Americans like because it's their culture or recent past history, such as that country music feel.

"If I sat down now, I could write the kind of song that Americans like to buy. Not to say they would, but every country loves its own reflection, it's that narcissistic thing. America likes that romantic, denim cowboy - expensive and cool in their music. Our music is different. We don't live American life-styles. I want to be successful for what we are. To everyone in England, everybody in America is either John Wayne or Farrah Fawcett. For Americans, every Englishman is Terry Thomas and every woman is the Queen".

"You can either change your music to suit American tastes or hope what you do will be acceptable without such a shift", adds Moulding. "Perhaps America should bend more than we should. For some bands, it's so important to be successful, they'll sacrifice their own musical satisfaction to that end. For us, it's not essential that we break here. We're not gonna worry about it. Musical satisfaction comes first. And, if financial rewards result from staying along our own course, all good and well. I'm glad we are what we are".

What XTC is is a band in the classic British pop mold, stretching back to the Beatles, Kinks and Small Faces. Between Andy Partridge and Colin Moulding, it has two distinct songwriters who excel in different areas.

"People say I write the melodic, softer, sweeter songs while Andy writes the more intellectual, phonetic songs", explains Colin. "But, if they care to look deeply enough into our material, they'll find I have written some intellectual songs and Andy has written some poppy tunes".

Indeed, on the Steve Lillywhite produced Black Sea, Partridge's love of rhythm and Moulding's affinity for melody, rather than cleaving up the LP in two, as with Drums and Wires, now exist side-by-side. Songs like "Towers of London" and "Burning With Optimism's Flames" show the two approaches finally achieving a seamless synthesis.

"I'd like to be considered in the tradition of bands like the Kinks and Small Faces", says Andy, "when bands weren't quite naive, but they had a sort of group feeling about them and were gently experimental and psychedelic within pop song formats. It was like they had this little round soap bubble which was the pop single and they just sort of pushed it slightly out-of-shape with experimentation. Perhaps it was a little bit of studio phasing or double-tracking or some other new technique of the time".

Is XTC an heir to the English art-rock tradition of Genesis, Pink Floyd and Yes, or is it closer to New Wave bands like Magazine, the Jam and the Clash?

"We are from working class families, which is supposedly where English punks come from", answers Colin. "And only Andy ever went to art-school. Our families are quite poor, but we've all got the other sort of tendencies, too. We've always had the art-rock appeal rather than street credibility.

"We know what it's like to be on the street and we don't want to preach about it. We've been through it, man, and we don't like writing about it. I don't care to glamorize it because it's just not nice. I like to write about the other side, the romantic side of life.

"XTC let people make up their own minds. We merely make observations. I'd like to think we're the Vasco de Gamas of popular music, exploring new grounds. This band has never really been fashionable at all".

Just as the English progressive outfits of the early 70s achieved commercial success, can't XTC eventually succeed with a steady diet of recording and touring?

"It's not quite cream floating to the top", suggests Andy P., "it's more like a being floated to the top, but it's transmuting all the time, so that when it does reach there, it's still gonna be brand new. I don't want to get to the top and be stale by the time we get there.

"I'd like to gently push XTC in the direction of more natural instruments marimbas, saxophones, acoustic guitars. Music that is quieter, but aggressively so".

If there is a single strand running through the current British art-rock, from Numan's Telekon to Joy Division's Closer to XTC's Black Sea, it is the increasing isolation being felt by England from the seat of world influence. As Great Britain adjust to its role as a second-class power, its music reflects the once-proud Empire's impotence in world affairs, especially on a song like XTC's marvelous "Living Through Another Cuba:" It's 1961 again and we are piggy in the middle ... Russia and America are at each other's throats / but don't you cry / just on your knees and pray and while you're / down there, kiss your arse goodbye / we're the bulldog on the fence l while others play their tennis overhead.

"Yeah, that's right, England's between the two big powers, like playing the ballboy in a tennis match", suggests Partridge. "The English Empire is well gone and people there do feel helpless when big things start stirring in the world. What can you do? Just wait to see what they dish us out.

"I think America will be like that in a hundred years or so. Like a comet that reaches a huge peak of success only to burn out... Egypt, Babylon, China... any of those huge empires that rose, went nova and collapsed".

There could be an analogy there to the rock world, with new, upcoming bands replacing the lapsed ones.

"Bands don't really have renaissances because they get too old", explains Andy. "A band's idea can have a renaissance, like The Who now are getting big again because they're called the Jam. The actual people don't have a renaissance, but the music styles do. And it can be just as powerful as the original thing".

Or as Gary Numan puts it, "And what if God's dead... We're independent from someone". But the best still goes on as England's latest generation of progressive rockers escape from this sociopolitical isolation to the creative isolation of the recording studio.

Go back to Chalkhills Articles.

[Thanks to David Oh]