Musician

Issue #127, May 1989

by Scott Isler

First, fly to London. Then catch a train to Swindon, 70 miles west. Then a cab from the station to a house in the Old Town section. Go through the door, up a flight of stairs. (Ignore the dog and two small children; you're not there yet.) On the landing, ascend a metal ladder through an opening to the attic. Stop. This is it: Andy Partridge's demo haven.

Whaddayamean, "so what"? Out of this small but fairly clean room have come some of the world's most cherished songs - "Love on a Farmboy's Wages", "Earn Enough for Us", "The Mayor of Simpleton" and at least one of the most detested, "Dear God". This is where Partridge, guitarist and main singer/songwriter of XTC, comes to escape his idyllic family life and plunge into the whirling ferment of his brain that feeds his band's curious existence. If these walls could talk, how frightening that would be.

In today's high-powered rock world, XTC stubbornly remains a cottage industry. And like most cottage industries that manage to survive (a dozen years, in this case), the band's developed its own way of doing things. Their drummer left over six years ago and they never replaced him. That's not as bad as it sounds, because XTC doesn't play five. They stopped doing that seven years ago; Partridge realized he had a phobia about appearing onstage, and he's refused to tour ever since. Still, XTC's previous album, Skylarking, was its most successful yet, helped by a song that wasn't on the record; it was a single B-side, and the band's record company had to reissue the album to include the "hit". Can't these guys do anything, er, right?

Well, yes: the music. Partridge's songs are dizzyingly intoxicating in their felicitous wordplay and sinuous, multiple-strain phrasing - although he can also deliver charmingly straightforward "pop" tunes. Bassist Colin Moulding, the band's other songwriter, complements Partridge's giddiness with more delicate melodies and more introspective lyrics about the human condition-though both writers are way beyond the superficial themes of more popular music.

Guitarist/keyboardist Dave Gregory, the most technically accomplished of the three, helps work up arrangements that at XTC's baroque best reveal new touches with each listen.

The resulting rich concoction may well be too much for the masses who determine this country's Top 10. But the band's attracted a loyal cult that supports three XTC fanzines in as many countries (and two languages), and whose members aren't afraid to invoke the Beatles in the same breath as Swindon's finest. They may even have a point: Both groups push the pop song into the realm of art while keeping a sense of humor. Perhaps the only thing the Beatles had that XTC doesn't was Beatlemania. It couldn't hurt.

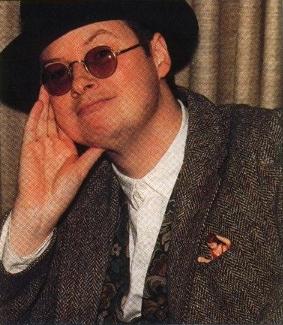

THE DUKES OF SWINDON: (left to right) Colin Moulding, Andy Partridge and Dave Gregory. |

"As a school kid I was totally in awe of groups like the Small Faces and Pink Floyd", Partridge remembers. "Singles like "See Emily Play", "Arnold Layne", "Itchycoo Park" - singles that had a high magic content: a three-minute thing of a very memorable tune but with a big dollop of magic injected, either some strange effect or totally nonsensical lyrics that painted great brain pictures. I did love psychedelic singles.

Oranges and Lemons, XTC's ninth album of new material, is a brilliant collection of songs that pay homage to Partridge's influences without slavish paisley revivalism. A nursery rhyme inspired the album title (which also unintentionally recalls Pink Floyd's "Apples and Oranges"), and a sense of childlike wonder pervades the 15 songs - from the burbling glee of the opening "Garden of Earthly Delights" to the dreamy conclusion of "Chalkhills and Children". Most amazingly of all, XTC recorded the album in Los Angeles - a mixture as friendly as spring water and strychnine.

"I never went out at all", Partridge says of his five-month stay. "I'm really anti-sun. Los Angeles is not my idea of a dream place to live. Everything about it I find rather 'waaaaah!' - from the weather to the people. I don't think I can honestly say I believed anything a Los Angeleno told me".

He seems more in his element sitting in his attic studio on a gray Swindon day in January, comfortably attired in a flannel plaid shirt, blue jeans and moccasins worn through at the big toe. There's nothing put-up about Andy Partridge; he's almost aggressively friendly. He's also the usual bunch of contradictions found in creative artists: a sharply clever individual who left school without papers or tests at age 15; a critic of warmongering political leaders who has shelves full of troops - battalions - whole regiments of toy soldiers; the composer of the sincere "Thanks for Christmas" and the militantly agnostic "Dear God".

Two years ago "Dear God" gave XTC its biggest publicity boost in the U.S. when some adventurous radio stations (talk about contradictions) discovered the song on the flip of a British single from Skylarking. Partridge says he didn't want "Dear God" on the album. He was dissatisfied with it because "it wasn't spikey enough; I thought it's got to stick in people's throats. It failed in that respect". (At least one Florida XTC fan, however, thought enough of "Dear God" to phone in a bomb threat to a local station spinning the song.)

XTC began its musical life in 1976 with much the same agenda. "We really wanted to annoy people, to get up their noses, " Partridge says of White Music, the debut album a year later. Partridge, Moulding and drummer Terry Chambers had been musically terrorizing Swindon under a variety of aliases since 1973. In 1977, with keyboard player Barry Andrews (since replaced by Gregory), they signed with Virgin Records, who probably thought they were getting a new-wave band. Despite a very occasional U.K. hit single over the years, they've had a rocky relationship with Virgin ever since.

The situation wasn't much better in the U.S., where XTC bounced from label to label. The band signed to Geffen Records in late 1983. Three years later Geffen was "rather despondent at the lack of sales", Partridge says, and tried to unload the band back to Virgin. The British company hadn't started up its Virgin America division yet, so it "panicked and said, 'No, keep them'. They didn't want to farm us around to other labels with a past record of no sales. Skylarking came out and Geffen just patted it on the back and sent it off-put it in a bag and threw it in the river".

Whether because of "Dear God" or in spite of it, Skylarking became XTC's best-selling American album, a sleeper that sold almost a quarter-million copies. Its corporate faith in XTC restored, Geffen actually seems excited about Oranges and Lemons. Typically, XTC hasn't made it easy, delivering an over-budget, hour-long album that needs a double-LP set to do it justice.

Strolling in the Garden of Earthly Delights: Dave Gregory, Colin Moulding and Andy Partridge stop to pick a bone with a fan. |

"I wanted to make a very simple, banal-sounding record," Partridge says ingenuously, "and it got lost in translation a little and came out rather multi-layered - in fact, very dense. We just got swept along with the enthusiasm: For the first time since our very first few albums, we were making an album that people actually wanted to hear."

Partridge wrote many of the songs just before the band went into the studio. Consequently, they tend to reflect his optimism over both his professional turn of luck and his burgeoning family: His daughter Holly is almost four, and a son, Harry, will be two this summer. On the other hand, he's also capable of scathing topical commentary like "Here Comes President Kill Again", "Scarecrow People" and "Across This Antheap".

"There is a bit of split personality", Partridge acknowledges. "On 'Garden of Earthly Delights', I'm trying to get a message over to my kids, although they'll have to wait some years before they can appreciate it: Somebody's being born and I'm saying welcome - like, 'Welcome to the Holiday Inn!' I'm in the foyer: 'This is life. Come in and do what you want to, but don't hurt anyone'". (The song's lyrics add, with Partridgian wit, "... Less of course they ask you".) "I'm sure that's what heaven is, really. Heaven is not hurting anyone".

So Andy Partridge, nonbeliever, believes in heaven?

"Yes. Here, now. This is heaven and hell. It's all metaphor stuff". But don't get him started on the subject of religion.

On the fatalistic "Here Comes President Kill Again", "I'm just saying, 'Go ahead, have your little bit of power and vote for who you want, but there's no difference'". Partridge says he "won't" vote: "I can't feel part of giving people that sort of power. There's a certain sort of person that wants to be voted in; it's almost like, if they're a politician, that's the very reason you shouldn't vote for them". This might strike some as an evasion of responsibility. Partridge feels, however, that "it's not like mankind can't find a better way. But I don't think mankind is smart enough to control itself yet. I totally distrust mankind, to be truthful".

The album's most affecting song may be "Hold Me My Daddy", a first-person plea for understanding between fathers and sons. "I found it difficult writing that", Partridge says. "It's a subject matter men aren't supposed to think about, loving their fathers. I played it to my father; he insisted on hearing it. We got to that point on the album and I had to leave the room: 'Hm! Is that the baby crying? I'll just go and have a look'. l came back, and I don't know if he was embarrassed or whether he really didn't hear the lyrics". Partridge adopts a gruff lower register: "'Couldn't 'ear a bloody word of that bloody row'. Maybe he did and he didn't want to say. It's sort of a primal oink, a sniffle".

Partridge's father was a musician himself, a drummer in jazz/dance bands. "I'm sure my parents still think I'm going to get a proper job one of these days. My father's sort of interested but he thinks it's too weird, too unusual - noisy pop music and loud guitars. My mother just likes it when people say to her, 'Oh, I saw your son in such-and-such magazine.

He himself disclaims fame. "I like people to buy the records but I'd be quite happy if we were faceless musicians and it was just the name XTC they bought, like a steak sauce. I always felt uncomfortable with fame. Howard Hughes is my hero". The self-described "Charles Laughton of the new wave - the last new wave" appreciates XTC's hard-bitten fans, even if he can't quite understand them. "It's like an odd-shaped mirror: very flattering to look into, but very weird 'cause it's so distorted and unreal".

Okay, Andy, we understand. Now, how do you write stuff? "Tricky to say. Deadlines can help scare music out of you. I always get this feeling that I'm never going to write another song. I'll sit up here staring at a blank page. Then some song will come out and it's complete... rubbish! Then a few more rubbishy ones come out. And then, suddenly, whaa! Something good'll come out. And whoa! Where'd this come from? It is like crapping; you have to get the blockage out of the way and then it all comes flowing out.

"Each time we finish an album I think that's the last thing I'm ever going to write. Then somebody says, 'Time for another record, isn't it?' The motors start clicking inside and I think, 'Hmm, have I got any songs?' And each time it's usually better than the last time out. 'Chalkhills and Children' is as good as anything I've ever done. 'Here Comes President Kill Again' is a fine marriage, the way the lyrics fit the music".

It's now time to meet Colin Moulding, who's been very patient. Moulding contributed three songs to Oranges and Lemons - thematic bummers, each and every one of them. (Though Geffen is considering the musically sprightly "King for a Day" as a single pick.) "It's the winter of discontent", he laughs. "If you're in a writing spree for two or three months, usually you don't feel up and down and up and down. I suppose it was more of a down period for me. I was just feeling really depressed. I think I've dragged meself out of it now. I tend to go through these, 'Oh, what's going to happen?'"

Moulding apparently labors longer over his songs than Partridge, which accounts for his smaller output. He had an unusually high percentage on Skylarking, a result of producer Todd Rundgren choosing the material. "I caught 'im and Todd holding hands a few times", Partridge says with malice towards none. "To be fair", Moulding quickly interjects, "we sent tapes over for Skylarking - I hadn't even met Todd - and the album running order was sealed". "It was a very weird sensation", Partridge adds, "to have somebody tell you what your album's gonna be, the order it's gonna be in, and how the songs will segue together".

"If I don't find playing live pleasurable, why be given money for something I don't enjoy doing? I might as well go sweep out the sewers". |

That was just the beginning of a clash of wills that marred Skylarking for Partridge. "The whole Todd experience was frustrating", he says. "We were obliged to shut up and be produced, or else; 'it's your last chance'. That was very difficult to swallow, and it put me in a belligerent mood from day one.

For Oranges and Lemons, Virgin Records was pushing the band to stay with an American producer - for dubious commercial reasons, Partridge believes. They chose the relatively inexperienced Paul Fox on the strength of a complete overhaul he'd done of a Boy George single. "The stuff they heard that I had done", Fox says, "was a little more mainstream than what they were used to doing". But Fox, an XTC fan, "knew that they did not exactly have a great time making their last album", and was determined to give them a better experience. He also had a valuable background in keyboards as a former session musician - and an even more valuable in at Los Angeles' Summa Music Group Studios, available to XTC for one-sixth the rate of the English studio that was their first choice. Partridge professes satisfaction with the results and Fox's respect. "It was nice to have somebody who listened to and tried our suggestions, even if they failed. It's difficult to play tennis on your own. You have to have somebody to whack the ball back; that's what keeps it going".

The drummer this time around was Mr. Mister's Pat Mastelotto, an old session-mate of Fox's. "I had known he was a big XTC fan", Fox says of the drummer, and he also thought Mastelotto's "bandier" approach - that is, less like an L.A. session pro - would fit in well with the group. "I knew that he could already play like Terry Chambers", Fox adds. Mr. Mister agreed to lend out Mastelotto, who had a blast requesting old XTC songs during the three weeks of rehearsals that preceded recording.

During those rehearsals Fox and the band arranged and restructured the demo recordings, which were in varying stages of completeness. Partridge admits his are pretty rough. "Sometimes you have a definite image of what you want. You hand the song over to other members of the band and say, 'Do what you will; I'd like this kind of atmosphere'. Sometimes they get it totally wrong and it can be surprisingly rewarding. Sometimes they get it totally wrong and they'll smother it".

"The Mayor of Simpleton", the initial single from Oranges and Lemons, started with lyrics Partridge wrote a few years ago. "It was a much more slow, mournful kind of song; early demos put it somewhere between UB40 and the Wailers, very reggaefied. It had a different tune, with much more of this miserable lope to it. I liked the lyrics, and I thought it needed vitality". "Across This Antheap" also accelerated from a bluesy tempo to its current "Latin" feel, according to Partridge - "from Tony Joe White to War". That's a sampled Partridge shouting "hey!" throughout. "I said, 'Look, can you make it sound like I'm shouting down a ventilator shaft?' The engineer said, 'Why don't you go and shout down a ventilator shaft?' The simplicity of ideas sometimes is astounding!" Partridge did, and that's what you hear.

One pronounced trait of Oranges and Lemons is the crisscrossing of vocal lines. "Countermelody madness!" Partridge exclaims. "It's just a habit we've gotten into - the joy of several songs happening at once. It's musical masturbation; I can't leave the thing alone. We feel like we sort of own it. Not many people do that now - not since West Side Story or South Pacific".

He notes that the three drummers on XTC's four post-Chambers albums "all have different personalities. Prairie Prince [on Skylarking] had a tight, flicky kind of sound - a very controlled feel. Pat Mastelotto was not afraid to use a lot of electronic bits and pieces, and not afraid to play along with machines; in fact, he encouraged it, which we thought was quite revolutionary in a drummer, 'cause drummers mostly think of machines as putting them out of work. He's very metronomic, and that underscored the precise feel to a lot of tracks on this album".

| Census Working Overtime by J.D. Considine |

|

He may (or may not) be the Mayor of Simpleton, but Andy Partridge knows one thing: The Roland PG-1000 programmer that goes with his D-50 confuses the hell out of him. "I'm not a very logical person," Partridge declares, and the PG-1000 "is aggressively logical and it rather upsets me." Until he figures it out, he's happier with a "tiny little Yamaha sampler" that he used for songwriting until recently. He seems to be having more fun with a new toy, a Alesis HR-16 drum machine. Partridge records home demos on a 1982-vintage Tascam Portastudio; for that purpose he keeps a "fizzy" Session MKII amp -- "not fantastic". He was impressed with a Fender Stage Lead he played through during the Oranges and Lemons rehearsals. Oops, guitars: Until '82 he played an Ibanez Artist exclusively, but that changed when he got a Fender Telecaster Squier -- "it has a nice clangorous tone" -- that's his current electric one-and-only. On the acoustic side, Partridge has played his Martin D-35 on all XTC albums dating from English Settlement. He also has a small Yamaha acoustic for "twanging" purposes, and a "Woolworth's" bass guitar (no name on the head) with a "very unusual tuba-like tone to it." Guitar strings are D'Addario or Ernie Ball Regular Slinky. Other gear: Korg DDD-1 drum machine, Yamaha D1500 digital delay, Alesis MIDIverb, Hitachi boom box. He has PG Tips teabags but prefers coffee. Colin Moulding used three basses on Oranges and Lemons, predominantly a Wal. Back-up basses were a Fender Precision and, for the double-bass sound on "Pink Thing", an Epiphone Newport. "It goes 'poun'," Partridge describes helpfully. Moulding's album rehearsal amp was a Trace Elliot -- "so clear it was unbelievable" -- and he holds his group together with Rotosound strings. Instead of a pick he prefers a fingernail (home-grown). He writes with the help of an Ovation acoustic guitar. Now if you want to talk guitar, ask Dave Gregory. He was crushed that he couldn't take his entire guitar harem (over 20) with him for Oranges and Lemons, but he made do with his faves: a 1953 Gibson Les Paul gold-top; a Schecter Telecaster-style ("quite versatile"); a 1963 Stratocaster; a semi-hollow 1964 Epiphone Riviera with miniature humbuckers, heard on the "Pink Thing" solo ("It has a nice Beatley sound"); and one of the first 25 Rickenbacker 12-strings shipped to England in the wake of A Hard Day's Night. Gregory uses Ernie Ball strings "out of force of habit," but creates his own gauge set: .011-.013-.016-.024-.038-.050. He has a Roland JC-120 amp "for those rare occasions that I go out of the house," and a Japanese Fender Sidekick 30 amp for home practice. Effects include a MIDIverb and D1500. For keyboard dabbling he keeps a Roland JX3P with MSQ-100 sequencer, and "an old acoustic piano." Co-producer Paul Fox called upon his background as a session musician to add some keyboards to Oranges and Lemons. He used mainly an Emulator III (e.g., the "strings" on "Across This Antheap") and, "for layering," a Roland Super Jupiter. He also employed an Emulator II, Roland D-50, PPG Wave, Prophet VS, Yamaha DX7, Oberheim Xpander, and his "museum rack" with an Oberheim 4-VC, Prophet 5, Roland Jupiters 6 and 8, and a Juno 106 MIDIed through a Sycologic box. Drummer Pat Mastelotto, a Yamaha endorsee, played on a Recording Series kit with Remo heads. But he obviously loves variety: He switched among eight different tom-toms (8" to 16") and 15 different snares. The 22"x16" kick-drum with a DW pedal pretty much stayed put, except for "President Kill"'s early-'40s Leedy parade drum; and on "Scarecrow People," featuring Mastelotto's old red Rogers -- was well as ashtrays and pots and pans to approximate Partridge's idea of a scarecrow drum kit. Cymbals tend to be Paistes for crashes, small (8", 10" and 12") Sabians for rides. "Scarecrow People" has an old K-Zildjian with rivets (courtesy of Fox); "Garden of Earthly Delights" includes a pair of 6" or 8" Sabian splashes. The high-hat was a 10" Sabian with a Paiste bell underneath. Mastelotto isn't shy with electronics. He used "a fair amount of samples" for composite snare sounds, including three alone for "King for a Day," played on a Roland Octopad, and the overtone of "a very ringy Ludwig similar to a tube-lug snare" sampled on an Akai S900. The drummer and his tech Paul Mitchell bent the samples with a warp function "to a note that sounded good" for each track. Tabourine-shaker, congas, tablas and other oriental percussion came from Casio FZ-1 samplers. A Yamaha RX5 drum machine crops up on the fade of "Hold Me My Daddy"; elsewhere Mastelotto used an MX8 MIDI patch bay to increase the velocity of a LinnDrum fed into a Yamaha QX2 program. An old Simmons SD55's kicks and snares are on "Chalkhills and Children" and "Poor Skeleton Steps Out." There's a Pearl SC-40 on "Cynical Days" -- "similar to a tambourine but more of a bongo" -- and "Garden of Earthly Delights," "for a low kick that bends up like a tabla." "Garden" also employs a Roland TR727 drum loop. And Mastelotto still uses sticks: Pro-Mark 5Bs or 909s, "butt-end." Finally, a few words of discouragement from Andy Partridge: "I don't take that much pride in instruments ... There's still no equation between better gear and better-quality songs, unfortunately." |

Doesn't Partridge ever long to have a permanent drummer?

"No, 'cause I wouldn't know what to do with him - bring him around once a week for a cup of tea and, 'See ya in seven months' time when I've written some songs, then!' We're not like the Monkees; we don't live in one big house".

Still, he likes the interplay of a band situation. "I need Colin to upset me, to bring demos around and for me to go, 'Shit, these are really good'. I need competition. If I was doing it all I'd get really lazy". He describes Gregory's role as "icing chef, decorating the cakes that we give him. He knows the chords I'm playing" - unlike Partridge sometimes.

With the album out, Partridge feels he's due for another bout of arm-twisting from Geffen to get him to tour. "They try that regularly. Someone gets very chummy, a few drinks go down, I get a little bit merry - and then he starts on a touring thing.

"I don't want to tour because I don't see that as pleasurable, and I don't see any reason at my age [35] to do anything or have anything inflicted on me that I don't find pleasurable. I should be in complete control of my life at my age, and do what the bell I want to 'cause I've earned the right - well", he reconsiders, "these various roads have led to the point in my head where I don't feel indebted to anyone; I don't have to follow any particular orders or instructions". He's speaking softly now. "If I don't find playing live pleasurable, why be given money for something you don't enjoy doing? You might as well go sweep out the sewers".

Partridge doesn't think XTC's "living death" as a studio band bothers Moulding, another family man. Gregory says he'd like to do more, "but I'm just a lone voice. These two guys are writing the songs and keeping the band afloat - if indeed there is still a band".

"He likes to play and crank it up", Partridge says of Gregory, "so I think he's a little frustrated. I've tried to urge him to go on the road with other people so he can get that evil spawn out of himself and come back and be with us". He switches on a broad west-country twang: "'You're not having sex in this marriage so it's all right to go to a prostitute if you want'".

He's suggested that Moulding and Gregory find another singer/guitarist for touring purposes: "I can stay at home and write songs and design stage shows for them. But I think that was a non-starter - we'd probably get all the Beach Boys shit flung at us. I've even considered getting a band together, calling them something like Farmboy's Wages, and they'd go out, like Beatlemania. It probably wouldn't be quite the same".

"They're really great live", says Fox, who had the privilege of being the entire audience at XTC's Oranges and Lemons rehearsals. He'd love to see a tour, though "I'm not going to hold my breath. They're all such good musicians". (Those with fading memories of exciting XTC shows will vouch for that.)

"I understand his - no, I don't understand his reasons for not touring", XTC manager Tarquin Gotch says of his recalcitrant charge. "I work on the assumption there will be no live touring, but secretly hope, in the back of my mind, some miracle might happen". Until it does, Partridge is likely to remain in Swindon, for which he harbors no great love. "The place is a dump, no romance about it. London is a bigger dump. I'd like to move out to the edge of the countryside, away from people a bit more".

It's not so much that adoring locals follow Partridge wherever he goes. "No, they probably resent the fact that we actually did something".

"Swindon's quite an apathetic town", Moulding concurs, "A lot of them think we split up, I think".

Only Gregory speaks for the defense. "There are pockets of people who are proud of what we've done on behalf of the town, I suppose", the soft-spoken guitarist says. "We put the town on the map".

Now, if only the public would put XTC on the charts. "It's sort of like a hobby, a paying hobby", Partridge says of his shabbily genteel career. He sounds incredulous when he notes that both Virgin and Geffen "are very happy with the songs we've given them. It's nice to have them positive for a change, rather than surly and saying, 'Well, I don't hold up much for the future if you don't get the sales figures up'. But it's funny: The more positive they get, the more unserious I get. They can sniff cash in it now, it's losing its appeal to me. If that redresses itself properly, I'll end up a house painter".

Speaking of hobbies and house painting, no XTC article would be authoritative without mention of the band's alter ego, the Dukes of Stratosphear. XTC almost was the Dukes of Stratosphear, but the shorter, snappier moniker won out the last time the group changed its name, in the mid-'70s. In 1979, Partridge asked Gregory - not yet in XTC, and an even bigger psychedelia nut than himself - "if he would be interested in making a psychedelic album under another name, like Electric Bone Temple".

That project was shelved until 1985, when Partridge dusted off the "Dukes of Stratosphear" handle for a remarkably authentic-sounding EP of pseudo-psychedelic ptributes. Partridge was pshocked to discover that the tongue-in-cheek 25 O'Clock sold twice as well as the previous XTC album, The Big Express. Virgin insisted "the Dukes" record a follow-up. (Geffen hadn't released the EP in the U.S.) "I'd told the Dukes joke and that was it", Partridge says, "But lots of letters came in; 'Can you ask the Dukes to do another album?' I relented, and I felt like we were doing The Empire Strikes Back, or something 'II'". The full-length Dukes album, Psonic Psunspot, contains better songs than its predecessor, Partridge feels, but with less of a period ambience.

In between these efforts, XTC proper was starting to play for real what the Dukes of Stratosphear did as a studied goof. The '60s aura of Oranges and Lemons makes it even harder to tell where one "group" stops and the other begins. Partridge hints darkly that he may have to "do in" the Dukes, perhaps "in a bizarre kitchen accident". Are the Dukes of Stratosphear the real XTC? Since his school days, Partridge had "wanted to be in a group that made that kind of music. It looks like XTC has now turned into that kind of group. We'll either get a damned good kicking because of that, or people will allow us to be what I always wanted to be. There was a split image and now they've merged".

Maybe the moon is in the right house now for XTC. They've got a striking new album, a pushy new manager and even some record-company interest. Too bad Partridge - proud but not conceited - doesn't share the enthusiasm.

"We're just like dough", insists Swindon's swami of simile. "What can you say about dough? We are the record, and nothing else".

That's the way he likes it.

Go back to Chalkhills Articles.

[Thanks to David Oh]