The British band XTC is about to kick off its first American tour since 1982, but the group's three members are not exactly ecstatic about it. The 13-city itinerary does not include any stadium dates. Or concert halls. Or, for that matter, any place with an actual stage and seats. Instead the trio will perform, live, from the studios of various radio stations. Even so, as they go on the air in Boston, they're sweating it. Their voices quiver and their perspiring hands stick to their guitar strings; “When that mike went on, it was scary,” says group leader Andy Partridge at the conclusion of a 40-minute set. “I couldn't move. I looked down and thought, ‘Whose hands are those?’”

No, he's not on Ecstasy. But maybe some XTC fan should remind him that those hands belong to the creator of some of the wittiest, most melodic pop songs heard on radio in recent years. At the moment, Partridge's “The Mayor of Simple ton,” an odd but appealing love song, is their biggest radio and video hit, and the trio has sold nearly 500,000 copies of its ninth studio LP, Oranges & Lemons. So why, with XTC nudging pop stardom after 12 years as cult heroes, are the lads so uptight about playing live on radio? Guitarist Colin Moulding, 33, and keyboardist Dave Gregory, 36, admit they're shy all the time. But Partridge, 35, though naturally gregarious, suffers from almost terminal stage fright. His battle with that malady peaked in 1982, when he panicked and couldn't go on at a Hollywood show. “I was forced by the manager to feign physical illness so promoters wouldn't have my legs broken,” he says. “The only good thing about touring was that for an hour you had a good sweat and a jump around. It was like a high-decibel sauna. But when I started to get stage fright, that ended it.”

The crescendo of anxiety that started in L.A. took more than a year to abate. For a long time, “I couldn't even leave my house,” says Partridge. “I thought I was on display. If I touched the doorknob to go outside and see the neighbors, I felt they were expecting some kind of fantastic individual.”

He might have been right. At home in the town of Swindon, west of London, where he lives with his wife, Marianne, 33, and two children, Holly, 4, and Harry, 22 months, Partridge spends his days reading 17th- and 18th-century English history, re-creating famous military battles with his army of toy soldiers, painting in a naïve folk style, dressing up like Long John Silver to entertain the kids and getting together every few weeks with Moulding and Gregory to work on what he calls XTC's “citric acid rock” music.

Partridge hates the word “quirky,” possibly because he has heard it so often. A precocious only child, Partridge learned early how to entertain himself. His father, a navy signalman, was rarely home, and his mother worked as a drugstore clerk. His pastimes included drawing, listening to Allen Sherman and Danny Kaye comedy albums and tormenting his mother. “I was always attempting to kill her in various ways,” he says, deadpan. “I locked her in the cupboard. She nearly asphyxiated. The milkman had to break down the door to save her.

By 14, Partridge had discovered girls, the Beatles, the Monkees and the guitar, a volatile mix. “The Beatles and the Monkees had good hair and they got women, so I wanted to play too,” he says. A top student, Partridge quit school at 16 and soon formed the first of several “loud and horrid” glitter rock bands that served his adolescent purpose. “The guitar was a fishing rod for girls,” he explains. “You stood onstage to hook girls out of the audience. It was an instantaneous sex passport.

In 1975 he cut his hair and, with Moulding, formed XTC, so named, says Partridge, because “we wanted to play short, sharp, shocking, wonderful music.” The first of many succès d'estime XTC albums followed in 1978. The next year, Gregory signed on “because I thought it would be something to tell my children about.” They finally got a U.S. radio hit in 1987, when college deejays began playing “Dear God,” a controversial song that, Partridge says, is intended to “challenge man's belief in God.” He regarded the song as one of his lesser efforts. Originally, “Dear God” had been released as the B side of another single. “It should have been called ‘Dear Man’ since in my opinion there is no God,” Partridge says. “It's humans that make stuff go wrong in the world. But I don't understand how such a simple, extremely unoriginal and timeworn topic could upset people so much. I've heard there have been threats to radio stations when they play the record.”

Despite the band's blossoming success, Partridge & Co., who all call Swindon home, have no plans to jazz up their decidedly relaxed life-styles. “There have been no cars driven into swimming pools by any member of this band,” boasts Partridge. “We're slipping quietly into middle age. It's the stupidest thing on the planet to try to stay teen age. It's pathetic when middle-aged men stagger around in clothes far too tight for them.”

Or dance around in videos. “I hate them all, including my own,” says Partridge. “Music goes in your ears, up to your brain, down to your feet, round your genitals and down your arms. But music is not for your eyes. XTC shouldn't have to make videos because what we purvey doesn't look glamorous. It's like cement. Cement is an interesting and useful article, but it's tough to make it look good.”

XTC

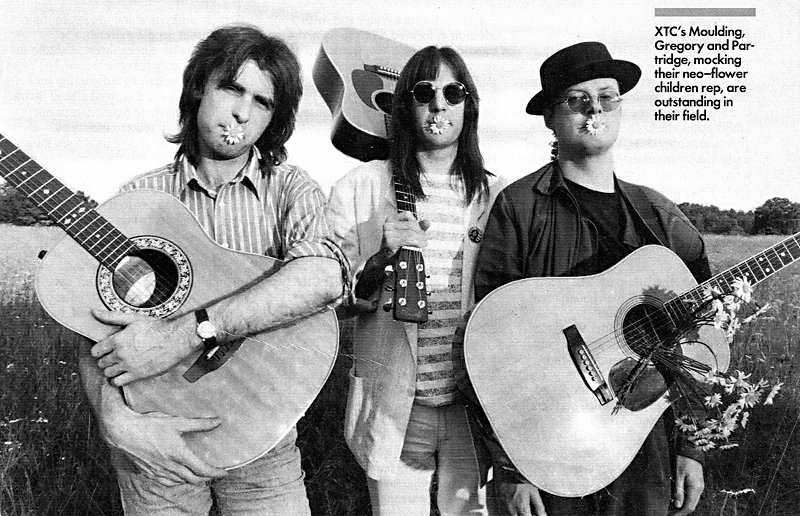

Dave Gregory, Andy Partridge and Colin Moulding—more than meets the ear

Photo Credit: Greg Allen

◼ XTC

A lot of people got a slightly skewed impression of XTC from the band's last and most popular album, Skylarking. Including the minor hits “Earn Enough for Us,” and “Dear God,” the 1987 album made this British trio sound like a basic pop band. Those who have followed XTC's 12-year career know better. Though the group members always wrote good mainstream pop songs, they typically offset every conventional note with a strange one. Oranges & Lemons brings XTC back to that old sweet and tart ratio. “The Mayor of Simpleton,” a love song about passion exceeding intellect, has all the marks of a standard pop hit. The rest of the double album can be just as appealing. For one thing, it's never predictable. One minute XTC is playing in a style that replicates the Beatles from the White Album era. The next minute the band switches to a weirder mode for a song like “Poor Skeleton Steps Out,” a danse macabre complete with synthesized xylophone sounds. Almost every song contains at least one catchy pop riff or chorus. Then those bright tunes abruptly shift into minor keys or unusual rhythms and harmonies.

[Thanks to Bill Wikstrom]